On the morning of July 1, 2015, militants engaged in coordinated attacks throughout Egypt’s North Sinai province. The attacks began just before 7 a.m. Cairo time, taking place at multiple checkpoints and other sites in the province, including a police officer’s club in the capital of Arish and sites throughout the city of Sheikh Zuweid (all sites of attacks are listed below). Islamic State affiliate Wilayat Sinai (formerly Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis) claimed the attacks in a series of statements, initially referencing “simultaneous martyrdom operations and attacks at more than 15 apostate army checkpoints,” and following with statements on six other attacks, plus additional combat locations.

The attack marks the most significant assault by militants in Egypt in many years, and for the first time, militants from Wilayat Sinai were able to gain control, albeit temporarily, of an urban center when they stormed Sheikh Zuweid. The number and length of operations, along with the ability to overtake multiple military installments and a heavily secured city with over sixty thousand inhabitants, are unparalleled in Egypt’s contemporary fight against terrorism.

By 12:40, militants declared that they had laid siege to the centrally located and heavily guarded police station in the city, which lies at the intersection of nearly one kilometer of closed roads, protected by checkpoints on the city’s outskirts. Throughout the afternoon, reports emerged of militants patrolling the streets and occupying rooftops of residences. (In several accounts, militants executed Sheikh Zuweid residents who refused to grant entry into their homes.) According to militant statements, suicide bombers targeted the checkpoints, allowing for an armed takeover of the city’s center and area south of there. In carrying out the attack, militants employed a range of weapons, deploying an arsenal of rocket-propelled grenades, Kornet anti-tank guided missiles, and mortars in coordination with roadside improvised explosive devices (IEDs) that disrupted the military’s ability to respond immediately.

The scale of the militants’ operations—the amount and type of weapons used, the broad geographic area of the attacks, and the number of fighters that would have been required—indicates significant advanced planning and coordination. The July 1 operation was the largest since a January 29, 2015, attack on the Battalion 101 military camp and a number of checkpoints in the North Sinai capital of Arish. Statements from terrorist media accounts said the Battalion 101 attack involved around 100 fighters, indicating that yesterday’s attack may have required a significant number more than that, given the increased number of checkpoints targeted and the militants’ ability to have overpowered military and held Sheikh Zuweid, even for a short period of 12 hours. The attack also demonstrates militants’ increasingly sophisticated organizational coordination into different units responsible for different locations and responsibilities (such as intelligence, security, operations).

The Egyptian military responded with great force. In the early afternoon, F-16 aircraft launched strikes on locations in and around Sheikh Zuweid. In a televised statement, the military officially reported 17 members of its forces were killed throughout the day (although government officials had earlier reported at least 50 security deaths to Al-Ahram). The statement also reported that the military had successfully killed more than 100 militants and destroyed 20 vehicles in its counterattack.

Militants reported over 100 soldiers killed in the operations. Restriction of communications due to downed cellular and electricity networks and the outright ban on journalists working in North Sinai have impeded any estimates of civilians wounded or killed in the initial assault or subsequent military response.

After the commencement of airstrikes, militants retreated from their positions in the city, reportedly evacuating amid continued air fire. By 7:00 p.m., Twitter accounts affiliated with Wilayat Sinai had admitted their defeat, vowing that their “humiliation” would not be in vain. Despite their avowal to continue attacks, the ammunition deployed in yesterday’s attack, combined with the blow to their numbers in the air assault, suggest that capacity to carry out large scale attacks may be severely hindered in the near future.

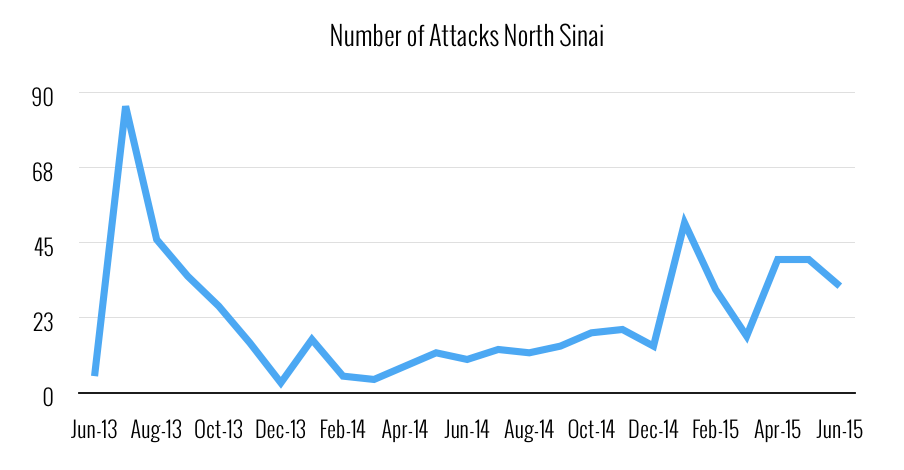

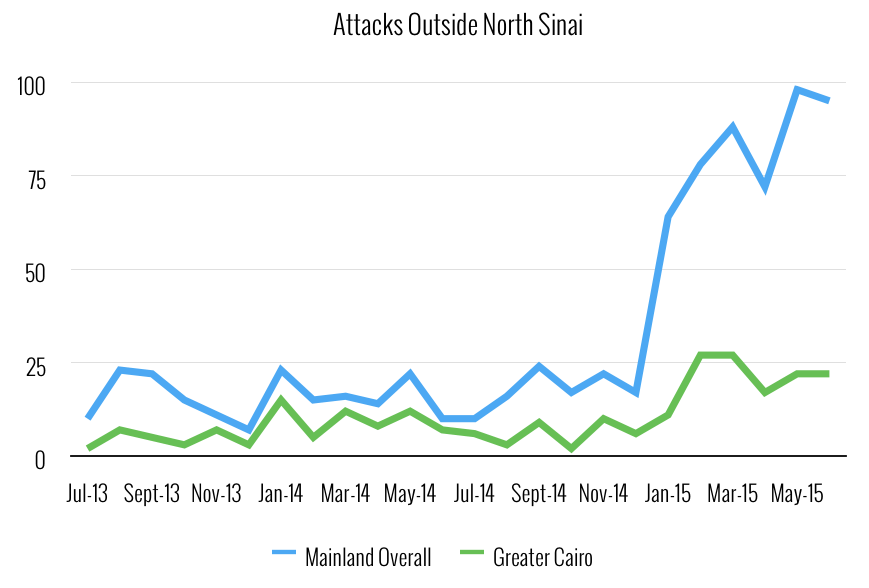

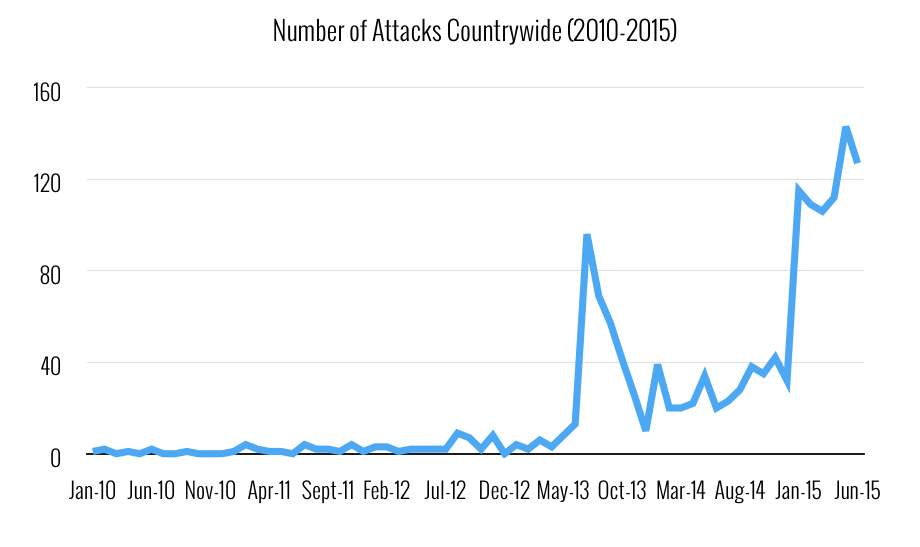

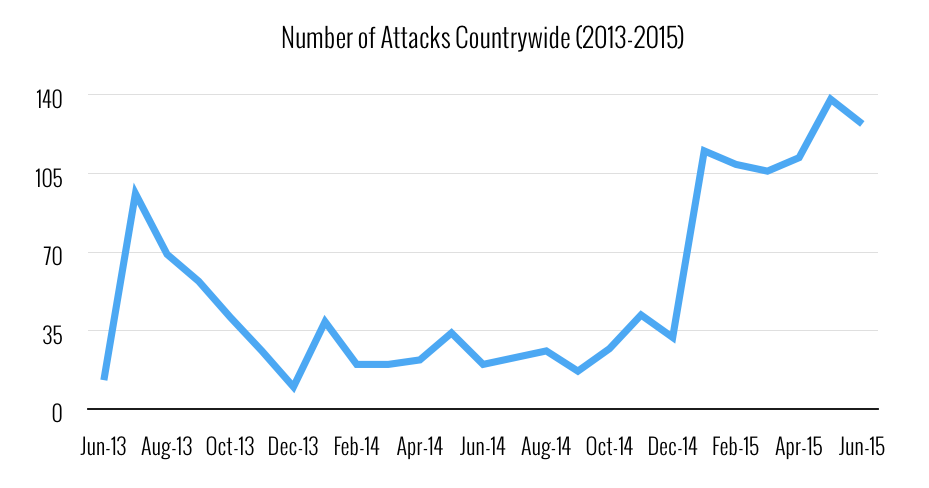

The attacks are indicative of the past nine months that have seen continuous escalation and heightened tension between militants and the military, particularly marked since an October 24, 2014, attack on soldiers at the Karm al-Qawadis checkpoint. The government’s creation of a buffer zone in Rafah, along the Gaza border, required the forced relocation of many residents. This evacuation, as well as airstrikes on militant strongholds (particularly in the Gaza border areas of Mehdiya and Moqataa), has led to increasing numbers of militant recruits.

The impact of the July 1 attack will remain to be seen in the upcoming days and months—not only in terms of the number of casualties, but also in terms of militants’ ability to operate. While militants expended significant weaponry throughout the day’s events, the extent of their caches remains unclear. After the fall of Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi in 2011, weapons flowed into Egypt through its porous western border. While these inflows have slowed significantly since mid-2013, several other factors may indicate large stores already in the country. The growing number of members and sympathizers are likely to join militant ranks with their own arsenals, given that the area is known for weapons ownership, and the militants have succeeded in capturing Egyptian military weaponry in attacks over the past months. Thus, while investigating and interrupting arms flows on the Western border is crucial to cut off terrorists’ resupply, it may not be enough to halt operations.

The real strength of Wilayat Sinai has come from their ability to exploit local frustrations with the military for their own violent means. In the Sheikh Zuweid attack, it was militants who were in the position of entering homes, forcing residents out, limiting their mobility, and causing civilian bloodshed. The placement of roadside bombs and militant attacks on ambulances attempting to enter the city prevented essential care from reaching civilians in desperate need. These factors now place militants in the position of antagonism toward civilian populations, a fact which has the potential to turn the tide of sympathy against them.

This situation provides an important moment for the Egyptian military to capitalize on an opportunity to engage with local populations to gather intelligence about militant operations. The inability to do so in the past has long been critiqued as a weakness that may have allowed for catastrophic attacks. Protecting civilians from militants without overreaching in the necessary efforts to root out and capture weapons supply could provide a turning point in the battle against insurgency in the Sinai.

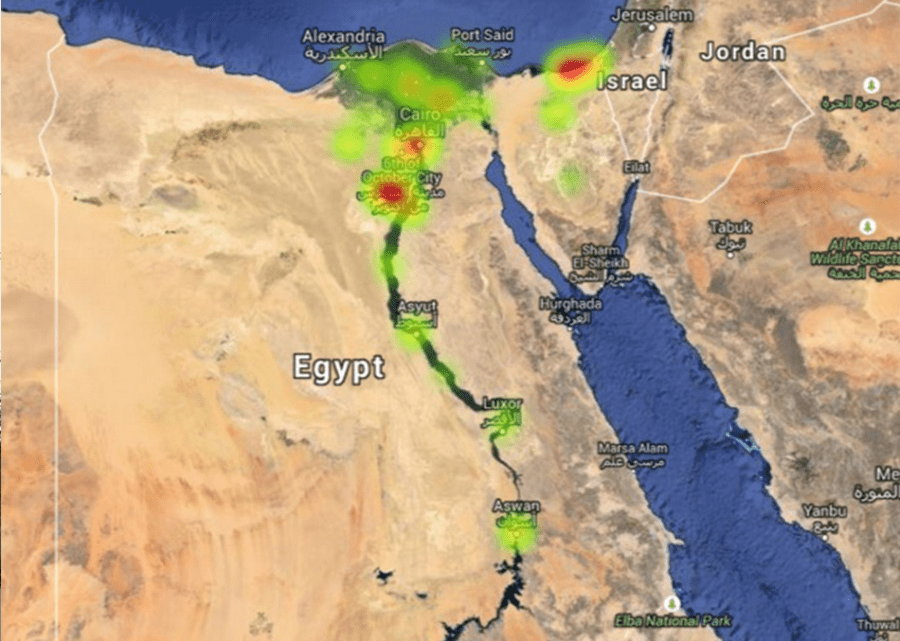

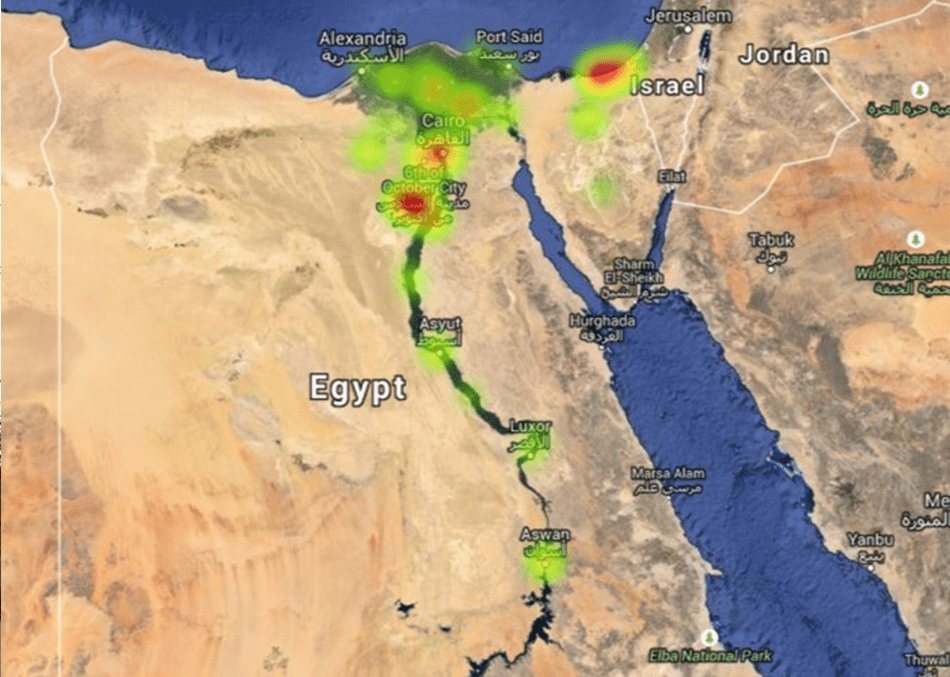

LOCATIONS

1 – Officers’ Club (Arish)

2 – Sadra checkpoint (Sheikh Zuweid)

3 – Abo Rifaii checkpoint (Sheikh Zuweid)

4 – al-Masura checkpoint

5 – Sadut checkpoint

6 – Wali Lafi checkpoint

7 – Wifaq checkpoint

8 – Abo Tawila checkpoint

9 – al-Dara’ib checkpoint

10 – Sheikh Zuweid police station

11 – Girada checkpoint

12 – Gas Station checkpoint (Kharuba)

13 – Abidat checkpoint

14 – Qabr Amir checkpoint

15 – Ambulance checkpoint

16 – Bawaba checkpoint

17 – Shilaq checkpoint

18 – Gorah checkpoint

19 – al-Zahir checkpoint

20 – Sa’id checkpoint

21 – al-Wahashi checkpoint