After a week of frenzied diplomacy to reach a cease-fire agreement and end the worsening Israeli offensive in Gaza, talks have ended almost back where they began.

By Sunday morning there had been meetings and phone calls between, in no particular order: Israel, Hamas, the Palestinian Authority (P.A.), Egypt, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Qatar, Bahrain, Turkey, and the United Nations. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas even rang up the Japanese to see if they wanted to play a role.

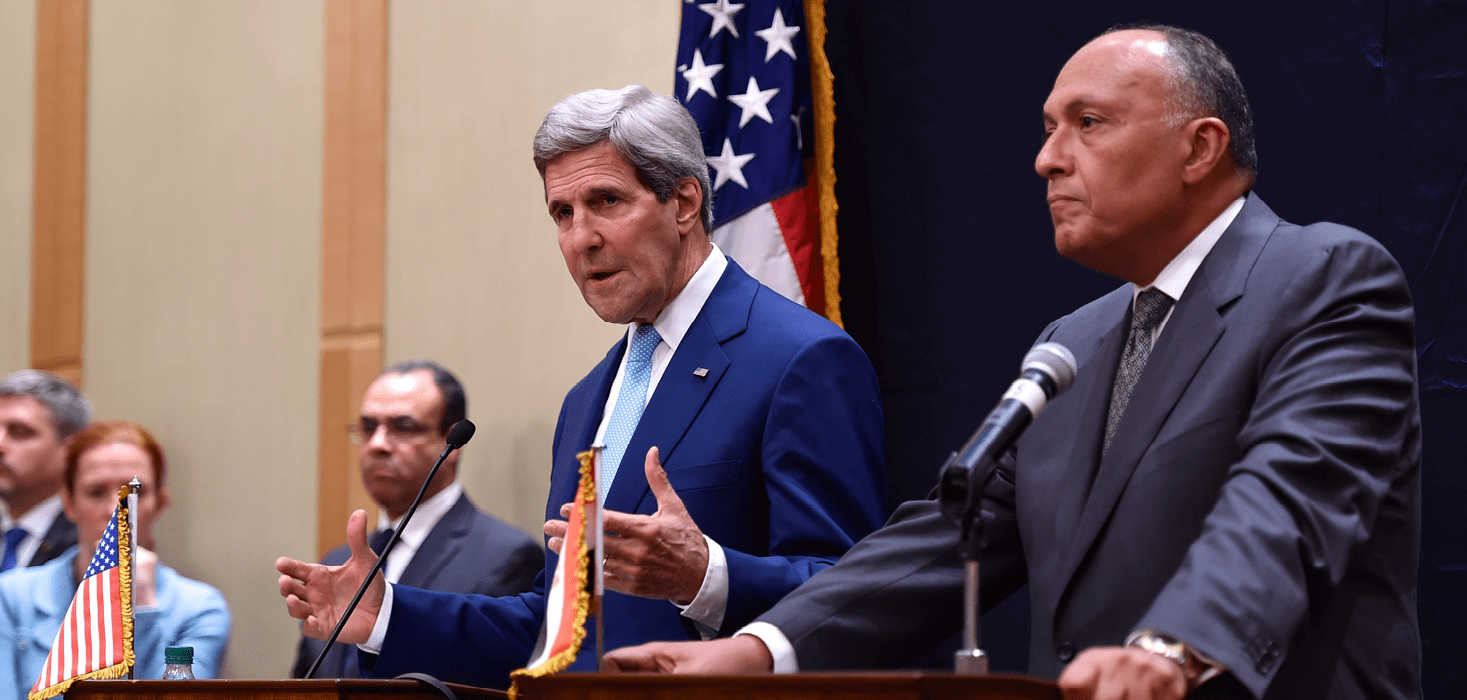

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry shuttled between Cairo, Jerusalem, and Ramallah, where he held meetings with three heads of state.

The end result of these meetings was a “Kerry proposal” that was not much different than an Egyptian proposal offered nearly two weeks ago. It called for an immediate one-week cease-fire and asked Israel and Hamas to dispatch envoys to Cairo for further negotiations.

There was one key difference between the earlier Cairo proposal and Kerry’s: The latter proposed American and European “guarantees” that negotiations will fulfill the demands of both parties—namely, the demilitarization of Gaza and the end of the years-old siege of the strip.

Nobody was satisfied with this proposal. The Israeli cabinet voted unanimously on Friday night to reject it, and after a 24-hour “humanitarian cease-fire,” it resumed its offensive in Gaza. Hamas dismissed any truce that would leave Israeli ground troops in the strip, and unnamed officials from the P.A. made it known that they did not like the deal, saying it would strengthen Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Thus the offensive continues well into its third week, with over 1,000 Palestinians dead, most of them civilians, and many thousands more injured. The Israeli army has lost at least 43 soldiers, more than triple the death toll from the 2008 war.

The drawn-out negotiations are a sharp contrast to the previous war in 2012, when the Egyptian government mediated a cease-fire with very similar terms in one week. Notably, though, the Kerry proposal strips Egypt of its role as the guarantor of the truce; instead it assigns the U.S., E.U., Qatar, Turkey and “many others” to monitor implementation.

Turkey and Qatar are, of course, Hamas’ main international backers, while the inclusion of the U.S. and E.U. is meant to placate Israel. Foreign ministers from the E.U. called last week to demilitarize Gaza, a key demand for the Israeli leadership.

The language, and the fact that Egypt was not invited to a Paris meeting on the cease-fire that was attended by its diplomatic rivals, Turkey and Qatar, suggest that the U.S. is edging Egypt out of its traditional role as the default mediator between Israel and Hamas. Like any state, Egypt was always a self-interested actor in brokering these truces, but this time Cairo’s ongoing crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas has made it more a party to the conflict than a negotiator.

The Egyptian proposal, first introduced on July 14, was the product of a telephone call between Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah El Sisi and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Hamas complained that it was frozen out of the talks and rejected the deal after learning about it through the media.

The proposal was not much different from the one that both sides readily accepted in 2012. Both proposals offered a return to the status quo ante, with a vague promise to ease the blockade “once the security situation stabilizes.”

President Muhammed Morsi took credit for the 2012 deal, though much of it was hashed out in private by Egyptian intelligence, which has longstanding ties to both Israel and Hamas. Khaled Meshaal, the leader of Hamas, traveled to Cairo to meet with then-General Intelligence chief Mohamed Raafat Shehata, as did Islamic Jihad chief Ramadan Shallah.

The agreement satisfied Israel, because it included no concessions, and boosted Morsi’s standing as a world leader (which he promptly squandered, issuing his infamous “constitutional decree” merely days later).

Hamas accepted the deal, but the promise to ease the blockade was never fulfilled, and officials said they were left feeling cheated.

Since the military retook power in Cairo last year, the army-backed government has reinforced the siege, destroying most of the smuggling tunnels on which Hamas relied for rockets and revenue.

This has become the central issue in the current negotiations: The Hamas leadership has been clear since the war began that they will not take any deal without meaningful changes on both the Israeli and Egyptian borders.

“We will not accept any proposal that does not lift the siege. This is the minimum,” Meshaal said at a press conference in Doha on Wednesday night. Meshaal singled out the border crossings “held by Arabs,” a clear jab at Cairo.

His obstinacy has not been well received in Cairo. “Egypt does not plan to make any adjustments to the initiative that was put forward a few days ago,” Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry said earlier this week. “We are convinced of the initiative.”

The Sisi government has spent the past year denouncing Hamas, an offshoot of the now-banned Muslim Brotherhood. It holds the group responsible for, among other things, helping to break Morsi out of prison during the 2011 revolution. More substantially, it accuses Hamas of assisting some of the militants fighting the Egyptian army in Sinai.

The continued fighting thus serves Egypt’s interests, as well as Israel’s: A weakened Hamas might be willing to change its tone towards Cairo and agree to concessions at the Rafah crossing. Egyptian sources say that Sisi is unlikely to reopen the border unless the Palestinian Authority takes control.

This idea has been floated in Jerusalem and Ramallah, too, with talk of Mahmoud Abbas’ presidential guard assuming responsibility for the border. Some Israeli officials have gone further, suggesting that the P.A. could control the entire strip.

“Abu Mazen’s people can take the responsibility for Gaza,” said Yaakov Amidror, Netanyahu’s former national security adviser, referring to Abbas by his nickname. “Whether they want to or not, I don’t know. But today there is no alternative.”

Kerry’s cease-fire proposal does not mention this, but the promise to “demilitarize” Gaza is a clear hint at shunting Hamas out of office. Dan Shapiro, the U.S. ambassador to Tel Aviv, told Channel 2 last week that “at the end of this conflict, we’ll seek to help the moderate elements among the Palestinians to become stronger in Gaza,” a reference to the P.A.

“They might be able to run Gaza more effectively than Hamas,” he added.

But Abbas might not be in a position to take control of Gaza, which has been under Hamas’ control since the violent schism between the two groups in 2007.

Two months ago, Abbas seemed to have the upper hand: He negotiated a “national reconciliation” government which included no cabinet members from Hamas, and the group began to hand over its control of ministries in Gaza. The tunnel closures had effectively bankrupted Hamas—it was unable to pay salaries—and it had few international allies, beyond Qatar and Turkey, the latter of which is increasingly preoccupied with problems outside of Palestine.

Since the war started, though, Abbas has been pushed to the sidelines. He kept quiet for the first few days before starting his own diplomatic push, with visits to Cairo, Istanbul, Doha, and Manama. None of them were very productive. The Palestinian Authority’s security forces, meanwhile, kept a lid on popular protests in the West Bank.

His popularity is now at its lowest point in years. Even within the Palestinian Liberation Organization itself, there seems to be a revolt brewing: Yasser Abed Rabbo, a senior member of the organization, said at a press conference this week that Hamas’ demands reflected those of the entire Palestinian people. The organization called for protests throughout the West Bank on Friday—though they did not materialize.

The unity deal, meanwhile, appears sidelined, and a newly-emboldened Hamas may reconsider the terms of the agreement after the war.

“If it ends the way the last two [wars] ended, then Hamas will not be in need of making such concessions to the P.A.,” said Ghassan Khatib, a professor at Birzeit University and former Palestinian government spokesman.

Abbas’ allies seem to be realizing the problem as well. “I think the Egyptians, and the Americans too, are trying to save Abbas by pushing him into the center of this,” one Israeli diplomat said.

“Egypt is trying to push Israel specifically to open channels with the P.A. to address this,” said Issandr El Amrani, the director of the North Africa program at the International Crisis Group. “It’s the opposite of how Morsi negotiated, where they sidelined the P.A.”

But it is difficult to see Cairo or Jerusalem achieving this desired outcome at the end of this conflict. Talk of demilitarizing Gaza is largely aspirational—something two Israeli wars and a seven-year siege failed to achieve. Both sides will probably have to make limited concessions on the borders, loosening the stranglehold on Hamas.

The Kerry proposal has received its own fair share of criticism: The knives came out for him on Sunday, with Israeli officials and columnists describing the proposal with words like “betrayal.” Netanyahu said on Monday night that he had no interest in a cease-fire which did not explicitly call to demilitarize Gaza. President Barack Obama’s call for an “immediate, unconditional” cease-fire went unheeded.

But Kerry’s diplomatic maneuvering, after more than a week of pushing the Egyptian plan, at least suggests that Cairo has lost credibility as an impartial mediator. Indeed, Israeli officials and analysts are openly talking about Sisi as a strong ally—and a participant in this conflict.

“This is not like previous conflicts, a confrontation between Israel and the Palestinian factions, but is highly connected with the ongoing struggle of the Sisi regime against the Muslim Brotherhood,” said Yoram Meital, a professor at Ben-Gurion University and an analyst of Israeli-Egyptian relations.

“Israel is looking forward to maintain this close coordination, and maybe even cooperation.”