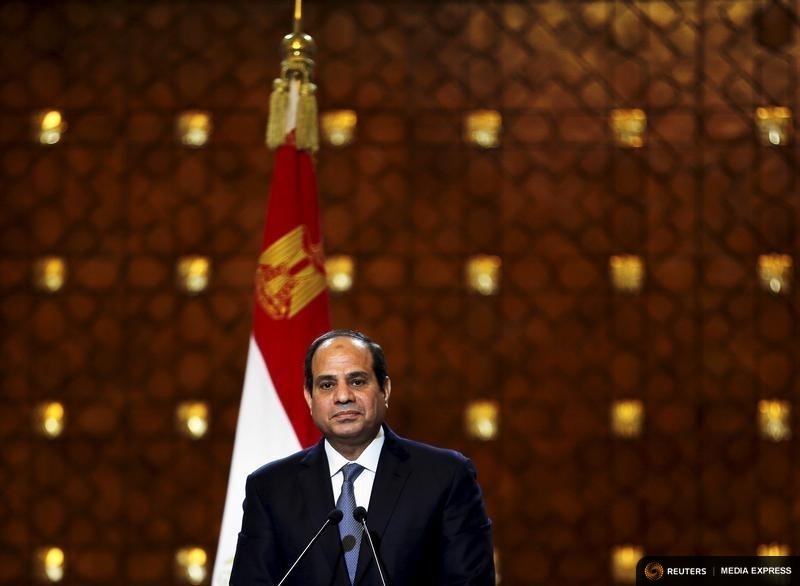

In the absence of a parliamentary body, Egypt’s constitution grants the president temporary legislative authority alongside his existing executive powers. President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi continues to regularly exercise this authority more than one year since his inauguration on June 8, 2014; today, he has ratified over 175 extraparliamentary laws and decrees.

With ongoing terrorist attacks and continued security concerns, a number of the president’s recent laws have focused on military and security affairs, as well as the consolidation of the state and its institutions.

Of particular note has been one recent law granting the Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Defense, and General Intelligence Agency the authority to establish security companies that provide protection services for public facilities and funds. The law further designates the Minister of Interior as the only individual capable of granting and revoking security licenses to private companies, and determines that security companies be owned solely by Egyptian citizens and operate only within the country’s borders. Although the state has a duty to protect national security, there are concerns regarding the adverse impact that such a law may have on the private sector’s security companies. The law also could potentially contribute to a military-industrial complex and unfair profit scheme for government agencies in a country where approximately one-third of the economy was reported to have been under army control in 2011.

Another recent decree appoints representatives of the Ministry of Interior and Ministry of Defense to the Legislative Reform Committee (( On June 16, 2014, President Sisi established the Legislative Reform Committee, a body tasked with preparing, researching, and studying draft laws and decrees issued by the President and the Prime Minister. While Article 153 of the Constitution grants the president general appointment authority, the creation of a body to draft and review legislation raises serious questions on the potentially extra-constitutional grant of authority handed down to an appointed body that would normally be accorded to the Cabinet or the House of Representatives.)). The committee—established by the president as an advisory entity to aid in the drafting of legislation in the absence of a parliament—is a manifestation of the president’s inherent appointment authority. The addition of interior and defense ministry representatives to the body reflects the roles that such entities are being allowed to play in the drafting of legislation.

Yet another newly ratified law grants the president the right to remove the heads and members of four financial and regulatory bodies in cases of harm to national security, breaches of duty to the state, and moral compromise. Under the constitution, these figures were not subject to removal save for exceptional circumstances set forth by the law. The new provision, which grants the president authority that seemingly contradicts with the internal bylaws of these regulatory agencies, thus endows the executive with heightened powers to remove individuals working on matters of corruption and financial supervision; the separation of powers and the check that such entities have historically had on government agencies may end up being compromised.

These recent decrees, a mere sample of the country’s newest pieces of legislation, reflect a trend over the last year to address serious national concerns through the consolidation of the security state and the constraint of citizen rights. The last year, for example, has witnessed a number of provisions, including but not limited to: the Terrorist Entities Law, which establishes a new process to designate terrorists under a vague definition; the designation of certain border regions as “prohibited;” amendments to the University and Azhar Laws on the removal and suspension of students and professors in light of their political activity; the introduction of a life imprisonment sentence for the receipt of foreign funds; the transfer of non-Egyptians to their countries for purposes of judicial extradition; and the trial by the military judicial system of civilians accused of committing crimes against public facilities.

Of course, the president’s legislative authority has also been used to carry out a number of important economic measures and day-to-day tasks. Over 20 treaties and executive agreements governing mostly matters of economic cooperation have been approved. Investment and Microfinance Laws promise an answer to years of economic stagnation. Improved housing schemes, social insurance structures, and taxation procedures have also been ratified.

Scholars argue that the temporary legislative authority that the president enjoys should be of an exceptional nature to accomplish only what is absolutely necessary for the nation’s well-being in the absence of a parliament. Under this scheme, the drafting and ratification of controversial and less urgent laws would be saved for the parliamentary process. This is especially true of circumstances in which the executive branch is effectively passing legislation that governs the executive branch.

Today, President Sisi is exercising authority in what appears to be an attempt to bring Egypt out of the throes of rising unemployment, economic faltering, and ongoing security voids through a number of vital measures. At the same time, he continues to issue legislation that disproportionately empowers the executive, judicial, and security arms of the state. Ideally, such legislation, which is neither urgent nor overwhelmingly popular, would instead be the product of months of parliamentary debate and drafting among legislators who are elected and represent the diversity of citizen backgrounds and interests. Instead, the country’s recent laws are the result of largely closed-door meetings between the president and a set of actors, none of whom are elected: the Legislative Reform Committee, the president’s various advisory committees, the Cabinet, and the State Council.

With a parliamentary elections schedule yet to be announced, such legislative trends are only likely to continue. In the time remaining, TIMEP’s Legislation Tracker, a tool set up to document nearly every extraparliamentary law and decree passed by the president and the legal context in which the decree exists, will provide a window into the executive’s temporary yet remarkable authority.