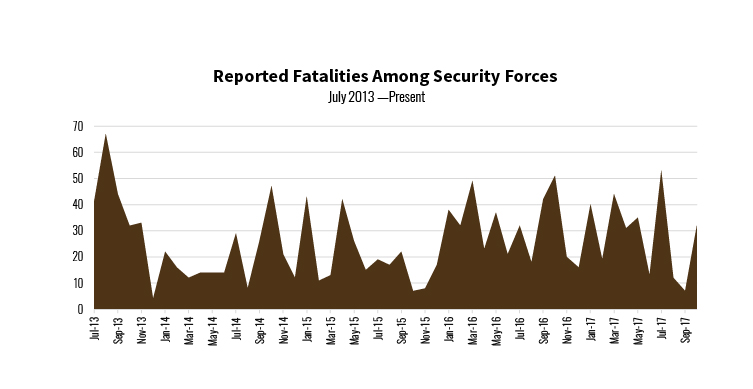

On Friday, October 20, a convoy of Egyptian security personnel attempting a counter-terror raid was overcome by militants near Bahariya Oasis, about 85 miles southwest of Cairo. The Ministry of Interior reported the deaths of 11 officers (including two brigadier generals), one sergeant, and four conscripts, with 13 injured and one missing. Other reports, relying on anonymous security officials, have placed the death toll at over 50. The convoy was responding to an apparent intelligence tip on a militant hideout when it was attacked, with militants executing the officers and conscripts and seizing weapons.

No group has issued a claim of responsibility, though Hassm, the Islamic State, al-Morabitoon, and militants affiliated with Ansar al-Sharia have all been mentioned as possible perpetrators.

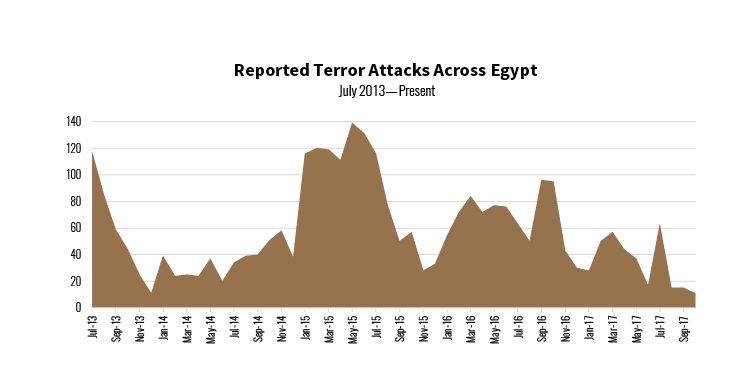

The attack is one of the deadliest events for Egypt’s security forces in its four-year war on terror. If independent reports are correct, it would be the deadliest since a July 2015 assault in which Islamic State militants briefly seized control of the center of the city of Sheikh Zuweid and attacked surrounding checkpoints. At least 255 attacks on security forces have taken place this year, in which nearly 300 police and military have been reported killed.

The day after the attack, Prime Minister Sherif Ismail addressed Egypt’s House of Representatives, declaring a renewed state of emergency as an effort to confront the “ugly face of terrorism.” The state of emergency was activated in April this year after twin attacks on Coptic churches on Palm Sunday, and grants the president the power to implement curfew, monitor communication, and censor the media. It also empowers Egypt’s State Security Emergency Courts to hear cases that, according to a separate decree from Ismail, may involve charges ranging from protesting to violating pricing rules.

Then, in a reshuffle a week later, a statement from the Interior Ministry announced the removal of top brass: 11 police generals, including two top-ranking officers responsible for security in Giza province, where the attack occurred, as well as the head of Egypt’s Homeland Security (its domestic intelligence branch and successor to the State Security Investigations Service). The presidency also announced the replacement of the military chief of staff, with Muhammad Farid Hegazy taking the post of Mahmoud Hegazy.

Context: “War on Terror”

- Egyptian military and police forces have been heavily engaged in counter-terror operations since the announcement of a war on terror in July 2013, with over 3,400 operations reported since the announcement. Much of the military’s attention has been focused on North Sinai, where over a third of security operations have taken place.

- Since the start of the war on terror, over 2,900 attacks have taken place nationwide, and more than 1,300 security personnel have been killed in attacks. Since that time, about 1,200 of these attacks have taken place outside North Sinai. In the Western Desert, there have been several reports of major attacks, the most notable of which was a July 2014 attack on a security outpost near Farafra Oasis, which killed 22 military personnel as they broke their Ramadan fast. More recent attacks have included a May attack near Bahariya Oasis that killed three security personnel, a May attack by the Islamic State on Coptic pilgrims that killed 28, and a January attack in New Valley that killed eight security personnel.

- Most of the violence from 2013 to 2015 was carried out by anonymous actors, though this has changed more recently: 58 percent of attacks in 2017 have been claimed by either the Islamic State or Hassm, both described later in this report.

- The Western Desert has also been a point of focus for military and police operations, both to counter terror groups and to crack down on smuggling routes that may bring militants and weapons to and from Libya. Counter-terror operations such as the one attempted outside Bahariya Oasis, the 2015 botched raid that killed a group of Mexican tourists and their Egyptian guides, and other intermittent reports of mass arrests or larger-scale operations, suggest that security activity there may be higher than is regularly reported in the media.

Context: Terror Groups

Reports have conflicting information on who may have carried out the attack, but have mentioned Hassm, the Islamic State, al-Morabitoon, and Ansar al-Sharia:

- Hassm: The attack initially was attributed to Hassm based on a claim purported to come from the group, but that was later discounted. Hassm is a domestic group that has carried out 16 attacks in Egypt since its inception in July 2016, including the attempted assassinations of former Grand Mufti of Egypt Ali Gomaa and Assistant Prosecutor-General Zakaria Abdel Aziz.

- The Islamic State: The Islamic State emerged out of the Sinai-based group Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, which announced its allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in November 2014 and assumed the name Wilayat Sinai at that time. As Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, the group had reported operations in the Western Desert in the summer of 2014. A year later, a July car bombing on the Italian consulate was claimed by the Islamic State in Egypt, which has carried out 21 attacks outside North Sinai since that time, killing 32 security personnel and about a hundred civilians. In September 2015, Wilayat Sinai also claimed activity in the Western Desert, releasing photo evidence of their convoys there and the beheading of an alleged informant that likely led to the raid that killed the Mexican tourists. More recently, the Islamic State in Egypt claimed responsibility for a May attack on Coptic pilgrims in Minya in the Western Desert in a wave of sectarian attacks throughout the country.

- Al-Morabitoon, the group of Hisham Ashmawy, who defected from Saeqa Special Forces and later became a member of Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, is believed to be linked to al-Qaeda. Al-Morabitoon has made no known claims for attacks, but Ashmawy is believed to have been connected to major attacks in Egypt that occurred while he was part of Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis prior to its announcement of allegiance to the Islamic State. Ashmawy faces charges in Egypt for planning the 2014 attack at Farafra Oasis. After this attack, Ashmawy broke with Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, was labeled an apostate, and crossed into Libya, where he declared the formation of al-Morabitoon, releasing several audio recordings in which he threatened violence in Egypt, but never claiming any operation.

- Ansar al-Sharia: Muhammad Sadeq, a former Egyptian assistant interior minister, said in a television interview that the police raid was meant to have targeted militants who crossed into Egypt from Libya and who were associated with Ansar al-Sharia. Affiliated with al-Qaeda, Ansar al-Sharia has been present primarily in Libya and Tunisia. An Egyptian branch that was active after 2011 was reported to be headed by Ahmed Ashush, with ties to Muhammad al-Zawahiri, though the branch is now defunct. Many Ansar al-Sharia members had also been linked to the Nasr City Cell, which has been tied to the 2012 attack on the American consulate in Benghazi. Ashmawy himself was reported to have lived in the same neighborhood as the gymnasium out of which the Nasr City Cell operated.

Analysis

The attack in the Western Desert raises many concerns about the persistent strength of militancy in Egypt, as well as the state’s struggle to maintain security despite its continued and ever-expanding efforts in its war on terror, which include security operations, enactment of emergency law, and restriction of information:

- While the group perpetrating the attack remains unknown, Hassm is an unlikely candidate, as it has never claimed any operation nearing this size, nor any in the area. The Islamic State has reported activity in the Western Desert as early as September 2015. Ashmawy’s knowledge of the area was demonstrated in the 2014 Farafra attack, and he would likely have connections with Libya’s Ansar al-Sharia through the al-Qaeda network, as well as potential connections from his time in the same neighborhood as the Nasr City Cell. Both Ashmawy and the Islamic State have demonstrated the capacity to carry out such large-scale operations, and the Bahariya incident suggests that the potential to strike despite years of counter-terror operations poses a grave threat to Egypt’s security.

- That the attack took place near Libya’s border is noteworthy, and highlights the unique challenge of securing border areas (as has also been seen in the struggle to eradicate the insurgency in North Sinai, which has been heavily focused on the border with Gaza). The flow of fighters, weapons, and other goods to and from Libya has been a point of heightened concern for Egypt since the fall of Muammar al-Qaddafi in 2011. Securing the border requires not only strong intelligence on militants operations and locations, but buy-in from local populations in the region who know these blind spots best, and who may otherwise be inclined to tolerate, deal with, or even directly support militant groups.

- Speculation about the attack suggests that the tragedy was due to misleading intelligence, though it is yet unclear whether intentional, and thus prevention of such attacks should include improvements in intelligence collection and analysis, and better identifying potential internal threats. Doing so requires allegiance from all levels of security personnel and relationships with local populations in surrounding areas, as mentioned above. While the removal of officials who fail to perform their duties adequately is important for accountability, without a fundamental review of the overall approach taken by the security sector, addressing due diligence, adherence to rule of law, respect for human rights, and effective intelligence collection and operations, such actions are only cosmetic.

- The emergency law was designed to allow authorities to declare a state of emergency and swiftly establish security during periods of inordinate violence. However, it does not appear to be the appropriate way to do so. While North Sinai has been under a state of emergency since 2014, the emergency law was not reactivated in the mainland until April this year. Since then, at least 28 terror attacks have taken place outside North Sinai, with up to 74 security personnel and 34 civilians reportedly killed. This amounts to an escalation of violence, considering that in the 12 months prior to the renewal of the law, 44 security personnel and 72 civilians were reported killed in 43 attacks. The emergency law fundamentally restricts rights and freedoms and grants the president sweeping powers intended only for temporary and extraordinary situations; its repeated extension appears to violate the spirit of the Egyptian Constitution, if not the letter, and rejects a central demand of the 2011 revolution to put an end to the emergency rule under which Egyptians had lived for decades.

- After conflicting reports citing anonymous security officials contradicted the Ministry of Interior’s official death toll, the State Information Service responded with a sternly worded letter in which it “condemned categorically [media outlets’] inaccurate coverage of this incident.” Egypt’s Media Syndicate suspended television anchorman Ahmed Moussa for airing tapes of police during the raid. Media freedom is heavily curtailed in Egypt, with a counter-terrorism law that criminalizes reporting statistics that differ from those in official statements, and, since May this year, over 400 websites have been blocked, including independent news media. A restriction of information to the public, through attacks on the press and the issuance of conflicting statements, will not lead to improved intelligence gathering or more effective counter-terror operations. Rather, such actions create a chaotic environment in which the public is robbed of the truth and their trust in officials is eroded.

- The attack at Bahariya Oasis, though domestic, demonstrates that while gains are made regionally in the fight against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, terror groups will continue to pose a threat, particularly in ungoverned areas and where the social contract between citizen and state has been eroded. The al-Qaeda network remains intact throughout North Africa, as in the Levant and Arabian Peninsula, and the Islamic State had previously announced its plan for inhiyaz, or retreat into the desert.

- Despite the gravity of the threat that terrorism continues to pose in the region and indications that the current security approach is ineffective, international support for it continues: the United States has provided Egypt with $1.3 billion in foreign military financing (FMF) annually since 2013, and European states have supplied arms in deals in excess of $3.26 billion during this time. However, announcements that $65.7 million of the FMF would be withheld this year and a potential $300 million cut in FMF appropriations for the next fiscal year signal a growing recognition of the important role of rights and freedoms in security approaches and the need to assess results and effectiveness of security assistance.