Summary: Since Egypt signed a multi-year 12.5 billion USD loan with the IMF in 2016, its government has dedicated its efforts to implementing wide-ranging economic reforms. These have included measures such as slashing subsidies, reforming tax structure, and removing currency controls, along with wide-ranging efforts to attract foreign investment. In this climate, China has injected between 16 and 20 billion USD into the Egyptian economy in the form of loans, investments, and development projects. These funds have been primarily invested in the infrastructure, energy, and telecommunications sectors, dedicated to projects such as the development of the Suez Canal Economic Zone, a light rail transit system connecting the new capital to cities outside of Cairo, and solar power stations near Aswan.

Through these initiatives, Egypt has become a strategic element of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. China launched the BRI in 2013 as a project to connect Eurasia through a strategic trade route, though it has now come to encompass more aspects of Chinese foreign policy. Although the BRI is mainly focused on East Africa, China has integrated Egypt and countries in Central and West Africa; Egypt has now become the fourth largest recipient of Chinese investment in Africa. China’s interests in Egypt have brought valuable revenue into the country, but their long-term social impact is unclear, and the strengthening of ties may facilitate rights abuses as China has interrogated and repatriated members of its Muslim Uighur community from Egypt.

Trend Analysis: Since the initiation of its BRI projects in Egypt, China has moved west along the Indian Ocean, acquiring ports and mainland stakes dubbed “the string of pearls.” Chinese companies, most prominently CHEC, have grown an empire of ports for a sum of over $12 billion. For Egypt, participation in the BRI and strengthening its strategic relations with China represent an avenue for prosperity, and in 2015, Egypt applied to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Although it is unclear whether Egypt was accepted, the move signaled the intended longevity of Sino-Egyptian relations. Yet given China’s propensity for secure investments, this longevity will depend on Egypt’s continued stability and relative attractiveness vis-à-vis other actors in the region (China has recently increased its investments in the UAE). At the moment, however, for Egypt’s traditional economic and diplomatic partners in the West, the increased prominence of China’s economic penetration in Egypt reflects a power rebalancing in the Middle East and across Africa.

Implications: Egypt’s external debt has been rising since 2014, reaching 92.64 billion USD in 2018, equivalent to 30% of GDP. Egyptian sovereign debt, which peaked at 102 percent of GDP in 2017, is now at 93 percent of GDP, exceeding the World Bank’s standard of 77 percent, which it considers the tipping point of economic growth. While the Egyptian government has committed to reducing the debt to 80 percent of GDP by 2022, an optimistic outlook attributed to the various mega-development projects (including those China is involved in), these projects are also posing a strain on Egypt’s macroeconomy as the government dedicates public resources and funding to these initiatives. While these projects may attract foreign investment and expand the private sector, holistically, the structure of the macroeconomy foreshadows an unsustainable trajectory for Egypt. Absent a clearly articulated and strategic economic development plan, it is unclear whether the sectors in which China has invested are those that will advance Egypt’s long-term strategic economic interests.

Additionally, the overall benefit of Chinese investments on the Egyptian socio-economy and for private sector growth are unclear. In accordance with both Egyptian law and its economic goals, FDI and development must be linked to increased participation of Egyptians in the workforce. While Chinese projects employ Egyptian labor, concerns have arisen throughout Africa that local employees are underrepresented in managerial positions, which may deprive them of valuable knowledge and skills transfer.

Finally, the human rights and security implications of cozier China-Egypt bilateral relations have already raised concerns. China’s dominance in the field of telecommunications, and particularly the expanding efforts of Chinese firms to install 5G networks across the world, seem primed to extend to Egypt (and indeed Egypt has promoted its investment landscape as fertile ground). These plans position China to set the standards for regulatory frameworks and potentially facilitate access to information that have raised serious rights and security concerns. Finally, Egypt’s tolerance for China’s targeting of Uighurs is likely to be only bolstered by the benefits it receives from Chinese support for its economy.

Legal Context: Articles 27 and 28 of the Egyptian Constitution commit the Egyptian state to “providing an environment that attracts investment.” While the constitution emphasizes the state’s responsibility to ensure that resources are utilized for the economic benefit of the country’s own citizens, Egypt’s Investment Law (Law No. 72 of 2017) stipulates that an investment project has the right to employ foreign workers up to 10 percent of its workforce. (In the absence of national labor of sufficient qualifications, the number can be increased to 20 percent.)

Several domestic and international legal obligations may be brought to bear on China’s interventions in Egypt’s economy. Per its constitution and commitments under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESR), Egypt is obligated to respect the rights of workers; however, the legal, judicial, and administrative environment has restricted these rights. Per the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, both Egypt and China should protect against human rights abuses within their territories and/or jurisdictions, including abuses committed by third parties like businesses; the Guiding Principles also govern the responsibility of businesses—Chinese firms in this case—to respect human rights. Chinese firms that partake in activities, including those furthering abuses to the right to privacy in the digital space or the right of workers to strike, for example, would occur in violation of this framework. While there has been little information regarding environmental degradation as a result of Chinese economic intervention in Egypt, this framework would also extend to the protection of the environment, of notable import given concerns around the environmental impact of development around Egypt’s new administrative capital.

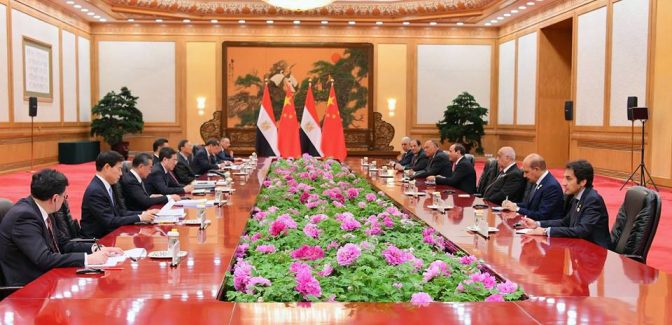

Political Context: Since the final years of Mubarak’s presidency, the Egyptian government has worked to strengthen and maintain close diplomatic and economic ties with the Chinese government. Though China slowed its investments in Egypt in the aftermath of the 2011 revolution, these were resumed when President Muhammad Morsi visited China in 2012; during the visit, the China Development Bank extended a 200 million USD credit line to Egypt. Since Abdel Fattah El-Sisi took office in 2014, he has visited China five times and hosted Chinese president Xi Jinping in Cairo in 2016. Sisi’s most recent visit was to China’s second BRI Forum in April 2019, just seven months after his last visit. The ties have also included security cooperation, in the form of joint naval exercises in August 2019, and Egypt has proffered support for China’s widely-condemned efforts to control its minority Muslim Uighur population; Egypt was a signatory to a letter of support for China’s efforts presented to the United Nations, has deported Uighur students since 2017, and recently facilitated access for Chinese officials to interrogate Uighurs in Egyptian prisons.

During this same period, the Egyptian government undertook economic reforms as part of the conditions to receive a 12 billion USD loan with the IMF. These included diversifying the economy, attracting foreign investment, and slashing energy subsidies. China’s interest in investing in Egyptian development complemented Egypt’s development trajectory and, in turn, Egypt has become an integral component in China’s BRI. In 2017, Egypt imported 8.1 billion USD in goods from China, more than any other country.

China’s projects in Egypt began with the establishment of the Chinese-Egyptian economic zone in Suez in 2008. The Tianjin Economic-Technological Development Area (TEDA) Industrial Zone was built in the Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZone). TEDA, built in the Ain Sokhna region, was planned to increase manufacturing and industrial activity in the area. China Harbour Excavation Company has contributed to developing the Suez region with the company’s construction of a container terminal in the Port of Damietta in 2018. The terminal has 2,225 meters long berths, a 17 meter harbor depth, and 700,000 square meters of container storage space. CHEC also began construction of a terminal basin in the Sokhna Port, a port area and industrial zone created by the Egyptian government to attract investment, the same year. SinoHydro, a subsidiary of Beijing-owned PowerChina, committed to help construct Egypt’s largest petrochemical facility, Tahrir Petrochemicals Complex in 2017, and in mid-2018 officials overseeing the facility confirmed that China had made 3.1 billion USD available for the project’s development. The complex was planned to be connected to the new Egyptian-Chinese Applied Technology College in Ismailia as a venue for skilled Egyptian labor for the project. Firms like Sinohydro and Dongfang Electric Corporation are also funding the Ataqa pumped storage hydroelectric power plant, with a 2,400 MW capacity, and a 6,000 MW clean-coal power plant in Hamrawein. With the success of these developments in the Suez region, China began expanding its enterprises to the country’s main cities.

The Chinese Railroad Corporation and China EXIM also announced they would contribute to constructing and financing a light rail transit system connecting the new administrative capital to cities outside of Cairo, though no timeline has been announced for its completion. The 1.24 billion USD project is expected to run 55 km and transport 350,000 passengers a day. This project goes hand-in-hand with China’s development projects in the administrative capital itself. China State Construction Engineering Corp (CSCEC) is building what it asserts will be the future tallest building in Africa in the capital. The skyscraper is one of 20 buildings the Chinese company is building in collaboration with a number of Egyptian construction companies in the capital’s business district. China is also beginning projects in the oil and gas sector through European and American companies like Apache Corporation. In 2013, Apache, a Texas-based oil firm operation in Egypt sold 33 percent of its company stock for 3.1 billion USD to Sinopec, China’s main oil developer. Chinese-Egyptian firm Sinotharwa is also 50 percent owned by Sinopec and operates 37 drilling rigs both on and off shore.

Chinese firms have also begun to make inroads in the telecommunications field, though not to the degree as in other sectors. Last year, Telecom Egypt secured 200 million USD in financing from Chinese banks, in a deal facilitated by Chinese telecoms giant Huawei. At the BRI summit in April of this year, Huawei signed a memorandum of understanding to develop a 5G network in Egypt; the company had previously signed an MoU to establish a cloud computing center in the country. It is unclear whether any progress has been made on either of these agreements—a similar announcement that Huawei would provide 5G services during the Africa’s Cup of Nations tournament in Cairo did not appear to come to fruition.