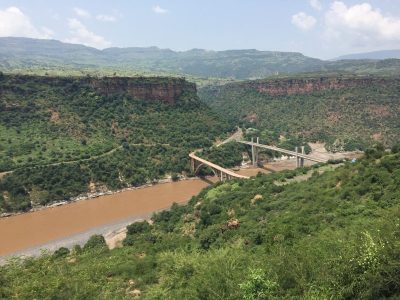

Summary: The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a 6,500-megawatt hydroelectric power plant being constructed in Ethiopia, has been a major point of contention between Egypt and its southern neighbors, as the completion of the dam poses serious threats to Egypt’s dwindling water supply and food security. Built along the Blue Nile in Ethiopia, the megaproject is viewed by Egyptians as a major challenge to Egypt’s historical claim to the Nile. Egypt’s agriculture sector has declined significantly in recent months, as Egypt reduced the amount of arable land nationwide for water-intensive crops and faced a shortage of crop production. This decline can be attributed to water insecurity and relations between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan remaining in a wavering position as the dam is built.

Political Context: Ethiopia began construction on the dam in 2011 in an endeavor to become the region’s primary energy exporter. The uncertainty surrounding the megaproject, specifically contention over the timeline in which the dam will be filled, has become a focal point of relations between Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan. Ethiopia has proposed filling the dam within three years, while Egypt has advocated a filling period up to 15 years. Former president Muhammad Morsi asserted with regard to the dam: “If our share of Nile water decreases, our blood will be the alternative.” While relations between the three countries normalized in the five years following Morsi’s ouster, negotiations hit a snag when Sudan recalled its ambassador from Cairo in January 2018 after Egypt’s rhetoric soured as the dam construction continued, though the ambassador returned to Egypt two months later after tensions cooled. In April 2018, Ethiopia appointed a new prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, who has been touted as a reformer. Negotiations reached an important breakthrough in May 2018 with a tripartite agreement regarding the dam. Though other agreements had been signed previously, political officials in each country hailed the May 2018 deal as the most significant to date. Under the deal, each country agrees to meet every six months on a rotating basis in their respective capital cities to discuss recent developments with the dam, though these meetings failed to occur as scheduled due to anti-government demonstrations in Sudan beginning in December 2018. A tripartite fund for the purpose of development projects was also established and a scientific research group was formed to study the impact of the dam on water resources.

Construction on the dam has stalled over the apparent suicide of the dam’s project manager in 2018, strikes by workers protesting insufficient wages, and the replacement of contracting companies because of delayed progress, all of which have occurred as Abiy attempts to implement reforms. Although the date of completion remains unknown, Egypt’s water scarcity raises additional political implications hampering the negotiations process. Political officials have described the dam as a “life or death” situation for Egypt and declared a state of emergency due to its shortage in water flow, which environmental experts have attributed to climate change, outdated irrigation techniques, and overpopulation. Egypt’s water insecurity, coupled with the threat of a filled dam, has led to additional crop imports, especially those that are water-intensive in production. Egypt’s wheat imports project to reach an all-time high for the country in 2019 with over 12,500 metric tons projected to be imported, maintaining Egypt’s status as one of the top importers of wheat worldwide.

Despite the previous agreements and construction difficulties regarding the dam, minimal geopolitical developments occurred surrounding the mega-project in 2019, primarily due to the Sudanese revolution. Negotiations between the three countries came to a halt upon the rise of anti-government protests and eventual overthrow of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir in April 2019. As civilian and military leaders worked through the formation of a transitional government in Sudan, officials in Egypt and Ethiopia provided monetary support, led negotiations between military and civilian groups in Sudan, and offered direction for the country in transition in part as a means of building rapport for future negotiations regarding the dam. Once negotiations finally resumed in September 2019, they became increasingly bilateral in nature, with Sudan assuming more of a third-party role. Negotiations reached a “deadlock,” as described by Egyptian officials with Abiy threatening to gather “millions” of individuals to defend the dam should hostilities emerge between Egypt and Ethiopia. The deadlocked negotiations and increasingly harsh rhetoric from Ethiopia prompted the United States to intervene and mediate discussions between the three countries in November 2019, where the three countries agreed to hold additional meetings in Washington and resolve the dispute by January 15, 2020.

Legal Context: The tension over the dam dates to the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement signed by Egypt and Sudan, which is based on the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty regarding the Nile. Under the 1959 agreement, Egypt is granted 55.5 billion cubic meters of water in the river as measured in Aswan, while Sudan is granted 18.5 billion cubic meters under the same conditions. Ethiopia, being excluded from the original agreement, has dismissed the pact in negotiations regarding the dam calling it outdated, while Sudan asserts that the agreement does not reflect its country’s current needs; meanwhile, Egypt has promoted the pact as its primary legal defense during discussions with the other two countries. Ethiopia, along with other Nile River basin countries, signed the Cooperative Framework Agreement in 2010 to establish formal governance over the river’s water distribution, but the agreement was rejected by both Egypt and Sudan as an attempt to reduce their respective water supplies. As part of the 2019 discussions based in Washington, the three countries agreed to invoke Article 10 of the 2015 Declaration of Principles if they fail to reach an agreement by January 15, 2020.[1] On a domestic level, Egypt safeguards the 1959 agreement through Article 44 of its constitution, which states, “The state commits to protecting the Nile River, maintaining Egypt’s historic rights thereto, rationalizing and maximizing its benefits, not wasting its water or polluting it. The state commits to protecting its mineral water, to adopting methods appropriate to achieve water safety, and to supporting scientific research in this field.”

Trend Analysis: Following the resumption of tripartite negotiations in September 2019, the future of the mega-project remains in a precarious position due to tense relations between the three countries. Though Sudan had increasingly aligned itself with Ethiopia to reap the economic benefits of the dam and increase its stake to the Nile prior to 2019, the new transitional government in Sudan has remained relatively neutral in the most recent series of negotiations. While Abiy’s status as a reformist and the May 2018 tripartite agreement shed a positive light for future negotiations, Egyptian and Ethiopian officials have dedicated additional attention in public comments to the dam in recent months. Furthermore, the accusatory statements by officials from Egypt and Ethiopia against their counterparts represent the greatest tension in the negotiations since Sudan recalled its ambassador to Cairo in January 2018.

Implications: The most prominent implications of the dam for Egypt pertain to Egypt’s agricultural sector and international relations. Though the dam is not yet complete, Egypt’s agriculture industry has already felt the effects of the megaproject coupled with its ongoing status as water-insecure: The country’s wheat harvest fell 350,000 tons short of its expected yield in 2018, prompting projections for 2019 that Egypt would import the largest amount of wheat in its history. These agricultural trends are expected to worsen once the dam becomes operational, as some experts predict that up to 60 percent of arable land in Egypt will no longer be suitable for agriculture after the dam is filled. Coupled with Egypt’s growing population and outdated irrigation methods that create overly salient water unfit for agricultural usage, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam may pose disastrous effects for the country’s agriculture sector.

While the dam poses pressing concerns for Egypt on a geopolitical level, these risks are overblown compared to the domestic problems associated with Egypt’s water insecurity. Under its current irrigation system, Egypt loses three billion cubic meters of water annually. Before attributing its water insecurity to Ethiopia to the dam, Egypt must address its outdated irrigation systems to yield more transparent negotiations between involved parties. However, the dam poses major economic implications for the region, as Ethiopia and Egypt both vie to become prominent regional exporters of energy resources, though Egypt has relied on nonrenewable resources such as natural gas compared to renewable hydroelectric power generated by the dam.

Sudan’s diminished role as deal broker in 2019 has created an opening and need for a neutral party or parties to support mediated negotiations, an opportunity to turn discussions around the dam’s construction from contentious politics toward solutions rooted in strategies for sustainable and equitable water management and lasting peace.

TIMEP’s Coverage:

“Pulling Back the Curtain: Dynamics and Implications of Egypt’s Elections Period – Phase III: Voting and Reactions” (TIMEP Brief)

“Ethiopia’s Dam and Egypt’s Water Woes” (TIMEP Commentary by Lindsay Carroll)

[1] Article 10 of the 2015 Declaration of Principles states: The three countries commit to settle any dispute resulting from the interpretation or application of the declaration of principles through talks or negotiations based on the good will principle. If the parties involved do not succeed in solving the dispute through talks or negotiations, they can ask for mediation or refer the matter to their heads of states or prime ministers.