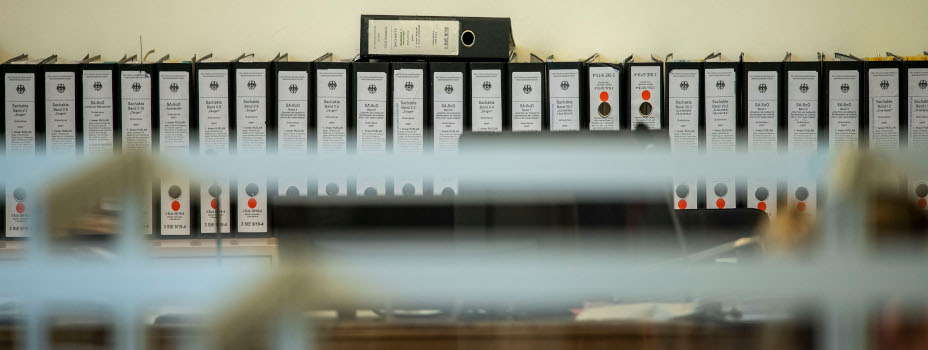

Since 2011, Syrian survivors, human rights defenders, and others have filed over 20 complaints in legal and judicial systems outside of Syria against Syrian regime officials for war crimes and other violations of international law. These complaints have been filed in reliance on the principle of extraterritorial jurisdiction, which allows foreign courts to exercise jurisdiction over crimes committed outside their respective countries. Complaints have varied. Some have been filed by or on behalf of victims or family members who are nationals of the country where the case was filed, while others have relied on a sub-principle of extraterritorial jurisdiction called universal jurisdiction, which recognizes that some abuses are of such immense severity that they concern humanity as a whole and can be prosecuted by any state willing to do so. While the vast majority of complaints have been filed in European countries from Germany to France and Sweden, one civil case has also been heard and litigated by a U.S. court. In one of the most recent high-profile developments in this space, on April 23, 2020 the first criminal trial in the world involving Syrian state torture began to be heard in Koblenz, Germany; proceedings are ongoing.

Analyzing these complaints, TIMEP has observed increased momentum for legal accountability, albeit amid certain political and legal challenges. TIMEP has also identified a number of trends in the justice space underscored by these cases and speaks to Patrick Kroker of the Berlin-based European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) about these trends.

**Note: While future content will address the legal proceedings involving violations of international law committed by non-regime actors, this interview focuses solely on cases involving violations by members of the Syrian regime.

TIMEP: Why are we seeing most cases in domestic European courts, as opposed to international fora like the International Criminal Court?

PK: First of all, the reason we see domestic prosecutions of the crimes committed in Syria in third countries is because these prosecutions are not taking place in Syria, neither now nor in the near future because the Syrian government is refusing to examine their own crimes. Second, on the international level, there would ordinarily be the International Criminal Court to turn to. However, that court only has jurisdiction over member states or if there is a referral by the UN Security Council. Neither is available here. Syria is not a member state and the last referral that was attempted in the Security Council in 2015 was vetoed by China and Russia. So the only availability for justice to be done that remains are prosecutions and investigations, mainly under the principle of universal jurisdiction in third countries. There are some countries that have taken the lead to investigate and prosecute under universal jurisdiction, most notably European countries such as Germany, France, or Sweden. Germany has played a leading role; it started investigations into international crimes committed in Syria as early as 2011 and now has an arrest warrant against Jamil Hassan – the head of Syria’s Air Force Intelligence, as well as an ongoing case in Koblenz against two regime officials accused of torture.

TIMEP: Most of the cases filed thus far have focused on torture of individuals held in Syrian regime detention facilities. Why is there a focus on this particular crime instead of others perpetrated by the regime?

PK: The cases against the Syrian regime have focused on torture, but that is not true of many Syrian-related cases prosecuting non-regime actors in Europe. Many of the non-regime cases have been tried under terrorism offenses.

In cases prosecuting regime officials, there are many reasons for the focus on torture. First of all, torture is prohibited, no matter the context and the particularities of the situation. Regarding other international crimes, for example the bombing or killing of civilians, it is sad to say, but these acts are not always considered criminal offenses in an armed conflict. There is though an absolute prohibition of torture. So the moment you torture somebody, it does constitute a violation of the Convention against Torture and if it is committed within a widespread and systematic attack against a population, it constitutes a crime against humanity. Second, torture is a crime that is relatively easy to prove as opposed to many other crimes because of the proximity of the criminal act to the crime site. That means the perpetrator, the victim, and the persons that are higher up in the chain of command are relatively close to each other. As long as they are in the same facility where torture is being committed on a widespread scale, then it is much easier to prove that the person was responsible for the torture taking place as opposed to many other crimes that have been committed in Syria. For example, with the use of chemical weapons, the crime site is far away from the place where the preparations have taken place. There is much more division of labor involved in committing these crimes. And from a criminal law point of view, it is very difficult to pin down who bears what kind of responsibility—someone chooses the targets, someone mixes chemicals, someone else loads them on an airplane, and again someone else pulls the trigger to release the weapons somewhere. So you have many more difficulties in proving many of the other crimes that have been committed. Another reason why the focus thus far has been on torture is because it is one of the most committed and emblematic crimes in the Syrian context. While these are the reasons for the focus on torture, of course, this is not something that necessarily needs to stay this way. Other cases are possible, and we hope that we will see them one day.

TIMEP: Very few cases have resulted in final judgments, but they include a civil case in the United States involving the targeted killing of journalist Marie Colvin and a criminal case in Sweden involving a low-level regime soldier sentenced to eight months. As some cases have begun to proceed, we’ve also seen the issuing of arrest warrants and the taking into custody of alleged perpetrators. What sort of remedy can criminal and civil courts provide to victims of abuses and what sort of punitive measures can these courts take, both as the cases proceed and at the judgment phase? In your assessment, why are these cases important? What would you say to someone who believes these cases move too slowly, are subject to too much politicization, or provide only piecemeal justice?

PK: It is a very wide and complicated topic to discuss what available remedies mean for victims. Deciding adequate remedies is highly individual and not possible to answer in a few sentences. I can begin by speaking about the measures that can be taken and result from these criminal justice interventions you mentioned in your question, especially the criminal ones. Because as you mentioned in the Marie Colvin case in the US, are one of the few civil cases we see.

The vast majority of the cases that we have ongoing are criminal case investigations against Syrian government officials. Of course these are criminal proceedings, meaning that in the end there is a prison sentence handed down, which is a punitive measure. For some people this is probably important to see that people are being punished for what they have done if they committed these crimes on a wide scale. I don’t think revenge is a primary motive. However, I think what is important is that there is an affirmation by our societies, and since we speak of international crimes, by the world and by the international community that this is unjust what has happened to Syrians and that this does constitute a grave crime. To give symbolic weight to this affirmation of what these people had to endure is a crime that is not tolerated by our societies or by the international community, it needs to be attached to a sanction. For that reason criminal cases can play a role. However, they only play a role to a limited extent and it is very important that they are accompanied by other justice measures. The implications [for criminal cases] can go beyond the law. Criminal justice often is the ice breaker for the transitional justice process.

For example, the statements, evidence, and findings presented in courts and court proceedings themselves possess authority and can help trigger other measures and steps toward justice. When a society is grappling with whether and how international crimes took place, criminal cases and trials can play some role by offering a narrative and establishing facts. At times, court judgements can empower people to take other forms of action as well. Artists, historians, and others, can take what unfolds in court and apply them toward justice in their particular spaces.

TIMEP: The vast majority of cases seem to be stuck in an investigative period years after the complaints were filed. Do you have any sense of why this may be the case and what can be achieved during these lengthy investigation periods?

PK: What I haven’t spoken about yet are arrest warrants because these are part of investigations and in many democratic countries, there are no cases in absentia against perpetrators. In Syria, for crimes committed by government, most people that carry the responsibility for these crimes are still in Syria. So they can’t be tried, but we can carry out investigations against them. This is important to prepare for future trials, to secure evidence, and also to have arrest warrants handed down. There is of course, with these arrest warrants, still a presumption of innocence—they only carry a preliminary decision on evidence. But they already carry an initial decision of a court of law or prosecutors, on the crimes and how likely it is that the persons who are named in these arrest warrants have committed these crimes. In Germany it is only with a high degree of suspicion that arrest warrants are issued. This means that the people that are affected by these warrants already have findings against them and are mostly likely limited from travelling because these arrest warrants can be enforced internationally. Somebody like Jamil Hassan from the Syrian Air Force Intelligence will now have to fear arrest and extradition to Germany or France when he travels. Obviously if the political situation stays as it is, not in Russia, Iran or some other countries, but in most other countries, and especially in European countries, it would be an obligation to extradite him to Germany. This already carries some form of restraint, or sanction, on them that these people are not used to. It is a step away, and a small one I will admit, but it is a step away, from the absolute impunity that these people normally enjoy.

These investigations are really important because they lay the groundwork for any future accountability mechanisms. If we begin to investigate only when the perpetrators are here in Europe, then it will take years from that point onwards. If you look at other international tribunals, it is always the prosecution and investigative unit that starts working first, and that work can take years sometimes before the actual trials happen. In Syria we are already at that stage. This early investigative period is essential because a lot of the evidence is outside of Syria and needs to be secured for future trials so that it can be shared with other prosecution authorities around the world.

TIMEP: A minority of cases have been dismissed, including in Spain or Switzerland. Is there concern that some cases may be stymied for political reasons, including the fear of some countries around expanding their extraterritorial and universal jurisdiction precedents?

PK: There are indeed some countries, including Spain, that have limited the scope of the universal jurisdiction laws. This has ultimately led to a case in Spain being dismissed. This is a wider political question that I do see as problematic. Also Belgium has limited its universal jurisdiction law and thus limits how far it plays into how these cases can be tried and investigated. We will have to see if this trend continues. In my view, the Syria cases are a very good example of why we need laws that permit such investigations, because we do have these atrocities whose horrors really speak for themselves, and I think nobody would really argue against the need to have criminal accountability for them. We see that there is no other option other than third states in these cases. So I would hope that it would lead to some countries to reconsider their laws and enlarge the application again.

TIMEP: Germany has one of the most expansive legal frameworks that allow for cases of this type to be heard. France also has a number of active cases. Do you expect that Germany and France will continue to be leaders in this space, and what role, if any, do both countries’ structural investigations play? Separately, what other countries have a hospitable framework for extraterritorial and/or universal jurisdiction and may be potential hosts for this form of legal action?

PK: As you rightly mentioned, Germany and France probably have the most active ongoing investigations. For the time being, it also seems likely to remain this way. This also has to do with these countries receiving a high number of refugees. Therefore there is a lot of information and evidence present. But also, these countries have high functioning war crimes units, which is one of the main prerequisites for these investigations to go ahead. And so I do think that for the next couple of years having investigations take place in Germany and France will remain a trend.

We are now working in some of these other investigations, there are other countries, especially in Europe, that can possibly play a more active role, and I hope they will do that. Most notably Norway, Sweden, and Austria, where we as ECCHR have filed complaints because we strongly believe that their laws permit investigations to go ahead and allow for the issuing of arrest warrants against high level perpetrators. In addition, the role these countries always claim for themselves politically, internationally, namely to promote human rights really demands that these countries become more active in leading investigations.

So I do hope that we see other countries join these efforts. Because really universal jurisdiction requires a piecemeal approach. It’s kind of like a big puzzle. And any country that has the possibility should really live up to his responsibility and find a piece of the puzzle that fits to contribute to the larger international effort.