The Egyptian Ministry of Defense posted a grainy video to its YouTube channel on Monday: A vehicle slowly approaches a checkpoint south of Arish. Nearby cars drive away and people scatter as a military tank crushes the vehicle, and presumably anyone who was inside. As the tank is driven away, a large explosion fills the screen—the detonation sends cars flying and covers the roadway in plumes of black smoke. “Success for the Heroes of the Armed Forces,” the video’s title trumpets, “thwarting a major attempt to target a security checkpoint.” No mention is made of the seven civilians, including two children, who were later reported to have died in the explosion.

The video represents a paradigm of Egypt’s war on terror, one in which the exception has become the norm, both when it comes to attacks and counter-terror measures: civilian deaths, a rarity in terror attacks merely two years ago, are occurring with much greater regularity. And the representation of success, regardless of outcome, has come to characterize the narrative of the Egyptian state when it comes to the war on terror. But how is success measured when dealing with, as the Egyptian government has consistently framed it, an existential threat? What is “necessary” to succeed against such a threat and at what cost does success come? What are the implications for the future security and stability of the country?

The episode comes almost exactly four years after Egypt’s war on terror was, for all intents and purposes, officially inaugurated. On July 24, 2013, then-Defense Minister Abdel-Fattah El Sisi stood behind a podium, resplendent in the trappings of full military regalia. Sisi promised to be Egypt’s savior and servant, and in this pivotal speech, he called upon Egypt’s institutions and citizens to support him in a mandate to fight terrorism. But the trends in violence since that time have paralleled both Sisi’s political trajectory and the pace of his repression, all three in a steady rise. Four years later, the answer to some of the aforementioned questions is abundantly clear: The war on terror has not made Egyptians safer, and in restricting the fundamental rights and freedoms demanded (and promised) in 2011 and 2013, it has kicked the can down the road when it comes to eliminating the scourges of violence and radicalization.

Yet yesterday’s headlines also trumpeted news of Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry’s visit to Brussels. Shoukry co-chaired the seventh European Union-Egypt Association Council meeting, celebrating a strengthening of ties that Federica Mogherini described as the “demonstration of the fact that Egypt is a key partner for the European Union.” Similarly, recent developments in the U.S.-Egyptian bilateral relationship—including budget and appropriations proposals that removed human rights conditions on $1.3 billion in security assistance and particularly Sisi’s recent visit to Washington—underscore a tacit endorsement of the manner in which Cairo has carried out its war on terror, as well as an explicit endorsement of the necessity of such a war.

The global consensus on the need to support Egypt in this war has been understandable, at least to a point. Undoubtedly, Sisi asked for a mandate at a moment when concerns were mounting over a new phase of instability: more than two years after mass protests brought Hosni Mubarak’s government down and months after they saw Muhammad Morsi ousted, a new wave of violence seemed to threaten the stability and progress for which Egyptians had sacrificed so much. Over 100 attacks took place in the three weeks prior to Sisi’s speech, sectarian targeting was on the rise as churches were burned, and violence was increasingly reported at political demonstrations and sit-ins.

Sisi’s speech, delivered at a military graduation ceremony but addressed to all Egyptians, signaled an escalation in efforts to address not only the violence that was occurring, but also what it immediately deemed as the source of such violence—the Muslim Brotherhood, which by the end of 2013 was declared a terrorist organization. Sisi asked the Egyptian people to take to the street to “do what is necessary” to support him and the security apparatus in confronting its enemies, a circle that has steadily expanded to include other political opposition members, civil society actors, human rights defenders, journalists, and even unlucky citizens in the wrong place at the wrong time.

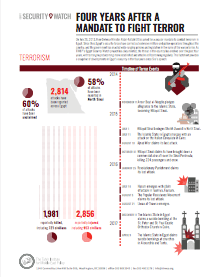

In the four years since the call for a mandate, the Egyptian Ministries of Interior and Defense have reported that they have killed 2,560 alleged terrorists in their war on terror, 96 percent of whom were killed during military operations targeting militants in North Sinai. They have claimed the arrest of over 16,000 terrorists, and have designated all manner of groups and individuals as terrorists, even those that have never committed nor aspired to commit acts of overt violence. Simply publishing statistics that differ from those of the government can be an act of terrorism.

As it did with the destruction of the tank, Cairo often touts these figures as signs of its success in its efforts, though it constantly threads a needle between demonstrating its competence in providing the security it promised in 2013 and maintaining the existence of the threat as a bogeyman, in the face of which it justifies its measures and curries domestic and international support for them. In truth, attacks have not abated but rather become more intense, if not always in number, in severity and loss of life, particularly for civilians. A total of 771 civilians have reportedly been killed in attacks in Egypt since July 2013, including 224 people killed on board a Russian Metrojet aircraft in October 2015—an act that had a reverberating effect on Egypt’s struggling tourist economy. Sectarian targeting has emerged with renewed vigor, and the Islamic State has carried out multiple attacks on churches and Christians in the past months.

While targeted policing and military efforts are certainly needed to identify threats, hold perpetrators accountable, and prevent attacks in the future, Egypt’s current approach too often relies on collective punishment that ranges from the blockage of media sites to extrajudicial killings. These types of counter-terror and counter-insurgency tactics have long been condemned by security officials and rights groups alike for the negative, long-term effect they have on radicalization and perpetuation of threats.

Thus, the great irony is that the ever broader-ranging, ever more constricting, and ever more extreme actions that the Egyptian government has taken in the name of its war on terror actually undermine the very objectives that it purports to achieve—and that the more the actions escalate, and the more violence intensifies, the more willing the international community seems to be to join in on Sisi’s call and give Cairo a mandate to do whatever it says is “necessary,” regardless of cost or consequence.

Instead of this carte blanche approach, a real investment in the security of Egypt (and the region) must come with the recognition that the approach used during the past four years has not worked, and the insistence that future measures include targeting of violent threats with appropriate use of force, legislative reform that specifically targets violent actors, and policies that respect constitutionally mandated and internationally recognized rights and freedoms. No matter how Cairo spins it, without a true 180-degree turn, Egypt’s war on terror will likely continue for many more years, at great cost to the Egyptian people and to the international community.