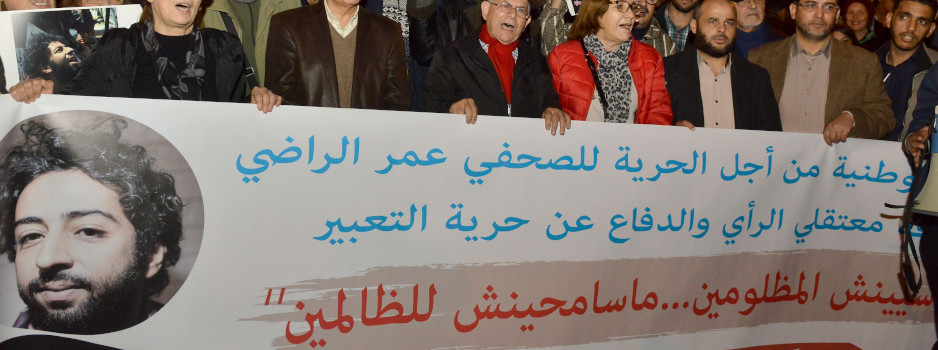

On July 29, 2020, Moroccan investigative journalist Omar Radi was transferred to Casablanca’s Oukacha prison pending trial in late September. Omar, who was summoned by the National Brigade of Judicial Police (BNPJ) for the tenth time since June 24, was immediately brought before the Court of Appeal and currently faces charges that include threatening national and international security, public indecency, and rape. These unrelated charges could cumulate up to 15 years of imprisonment.

Omar’s case, while containing unique specificities, fits into Morocco’s sophisticated propensity to use intimidation, threats and prosecution against journalists, human rights activists and dissident voices, whilst alienating them from the public’s sympathy. Continuous harassment, coupled with speedy trials and lengthy sentences, is a strategy that has exponentially increased since the enshrinement of Prosecutorial Independence, a 2017 reform that granted tremendous powers and little accountability to prosecution—and which coincided with the crackdown on the Hirak al Rif protesters. Moreover, charges brought against journalists often have little to do with their work, but rather stem from the unjustified intrusion of the authorities in these individuals’ intimate lives. Such intrusions are instrumentalized to coincide with the real motives behind the decision to prosecute.

As domestic and international civil society organizations attempt to shed more light and interest around Morocco’s stifling of press freedoms, the Kingdom shows little mercy towards its critics. In light of the social demands and economic constraints hampering the regime’s public image, the government’s response to opposition—one which rests on defamation and prosecution—has already begun to amplify resistance to the status quo in lieu of durably silencing critical voices.

The authorities’ repeated harassment of Omar Radi began several months back, leading to the journalist’s first round of pre-trial detention on December 26 of last year. He was charged with contempt to a magistrate over a tweet that he shared months before, and for which he served a four-month suspended prison sentence—largely thanks to international outcry demanding his release. Since then, the campaign launched against Radi has gained unprecedented momentum, culminating in a fascinating turn of events and ludicrous claims following the release of an Amnesty International report accusing Morocco of using NSO’s Pegasus spyware to infiltrate Omar Radi’s and ex-political detainee Maati Monjib’s phones. In the rare move of a state threatening to sue an international NGO, the Ministry of Human Rights immediately deemed the report unfounded and demanded material proof for the accusations brought about in the report. More critically, the authorities, in turn, accused Radi of receiving funds from a foreign agent, accusations that circulated in detail across makhzen platforms before formal judicial investigations began to take place.

To date, Omar’s case embodies the critical situation of rule of law and freedom of expression, as never in Morocco’s recent history has a journalist been accused of such an exceptionally broad spectrum of charges, little to none of which fall under the Press Code. Additionally, the demonization campaign launched by the media leaves no room for society at large to sympathize with Omar’s conviction, possibly to further dissociate him from the more romanticized journalists who managed to garner a strong popular base though their criticism of the regime.

Indeed, the current strategy draws the picture of a deviant journalist unworthy of public support. The pool of accusations reported in the media against Radi range from public intoxication, violence and rape to contempt to court, disrupting national integrity, threatening national security and so on, enough to assuage both international and domestic support.

Commonplace in politically-motivated trials, rape charges and other accusations of indecent behavior are an alarming tactic that seeks to break up solidarity networks and ostracize the accused from a relatively conservative Moroccan public, as well as from feminist movements, locally and abroad.

Journalist Hajar Raissouni, who was sentenced along with her husband and medical corps to a year of prison time for abortion and unlawful sexual relations, was among the latest journalists to fall prey to such methods. Still, the consistent use of these practices over time has left little confidence in the Moroccan justice system for the public to continue to believe these claims. The selective prosecution of rape charges and its instrumentalization in politically-charged trials causes great harm to women’s battles for social justice and is greatly detrimental to the victims of sexual crimes. Within the broader context of how such charges have been used in the past, when it came to Omar’s case, the rape charges did little to back off proponents of freedom of speech and human rights observers. Hajar Raissouni expressed her support with Omar as well as with the other journalists accused of similar crimes, including her uncle Souleyman Raissouni, currently sitting in jail for a rape claim from 2018 made over a Facebook post and editor Taoufik Bouachrine, whose rape trial and 15-year sentence were intensely followed and debated in the media.

A Moroccan group, the Mostaqillat also circulated a petition condemning the instrumentalization of feminist causes. Another group of over 400 artists and cultural personalities have signed a petition against police repression and arbitrary arrest, alongside other sprouting movements mobilizing against the defamatory press lynchings in Morocco, and for more rule of law in the treatment of journalists and private citizens alike. More interestingly, solidarity networks are forming across the region to shed light on the erosion of press freedoms and the rise of arbitrary detentions in MENA in recent years.

Days before Radi’s arrest, Hamid El Mahdaoui, editor-in-chief of critical online platform Badil.com was released after spending three years in prison for failing to inform the authorities of an imminent threat to national security. El Mahdaoui, who garnered a strong support base through his online appearances and relatable elocution style, likely served as a case study of good practices in the way the makhzen media handled the case, which made every possible attempt to distance Radi’s case from El Mahdaoui’s.

Upon his release, El Mahdaoui drew a daunting picture of prison conditions and of the treatment to which he was subjected personally—including lack of access to medical care. Promptly denied by Morocco’s Prison Authority, El Mahdaoui’s post-release statements nonetheless launched an overdue discussion on prison conditions and the reform of penitentiary institutions.

As Radi awaits trial on September 22, there is little faith in a prompt conclusion to the systemic crackdown on opposition figures. To restore the constitutional promises of a free and independent press and civil society, the Moroccan state needs more than simply reforming its judiciary and institutions. A thorough restructuring of the media as well as the creation of binding legal frameworks against defamation in the media and online are necessary steps to take. In order to avoid reliving the past and in order to align with the image the kingdom is desperately attempting to showcase, it is not only Morocco’s judiciary that needs a shake up, but the whole governance model that needs urgent revisiting.