On May 8, four men carried out a brutal mass shooting, emptying their magazines into an adjacent car as they drove along the Nile in Helwan, a district in Cairo. Eight policemen were killed during the attack, which was claimed by both the Islamic State in Egypt (that is, the branch of the global organization that operates in mainland Egypt, rather than Sinai) and a lesser-known group, the Popular Resistance Movement. Our long-term research shows that violence like this has been thriving in mainland Egypt for years. While the insurgency in the restive North Sinai has garnered a great deal of concern, actors in the mainland (that is, outside of Sinai) have evolved since then-Defense Minister Abdel-Fattah El Sisi asked for a popular mandate to counter terrorism in July 2013, and those actors continue to carry out regular attacks across the country.

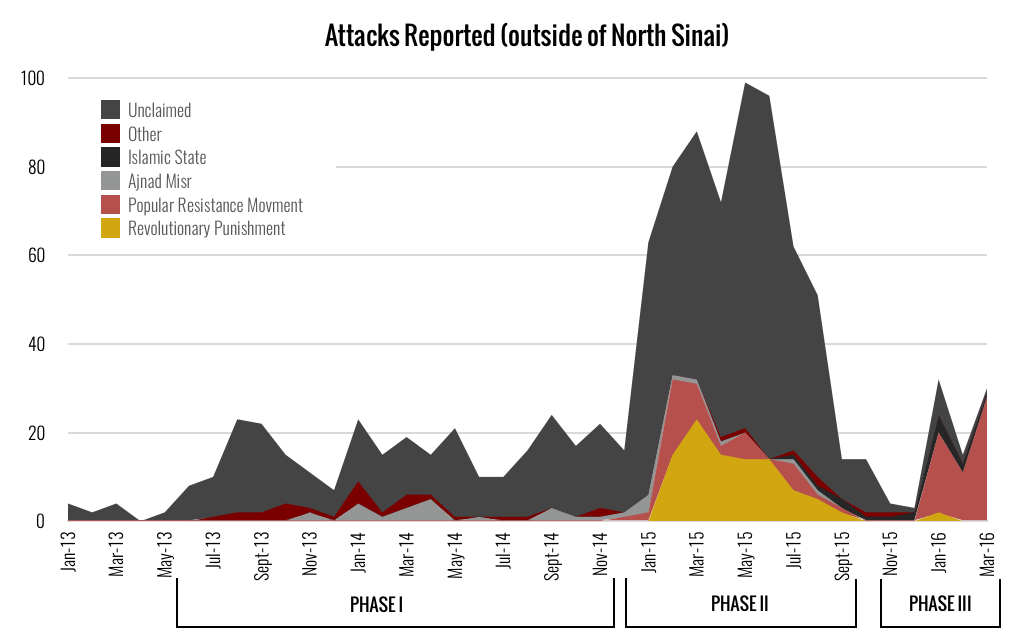

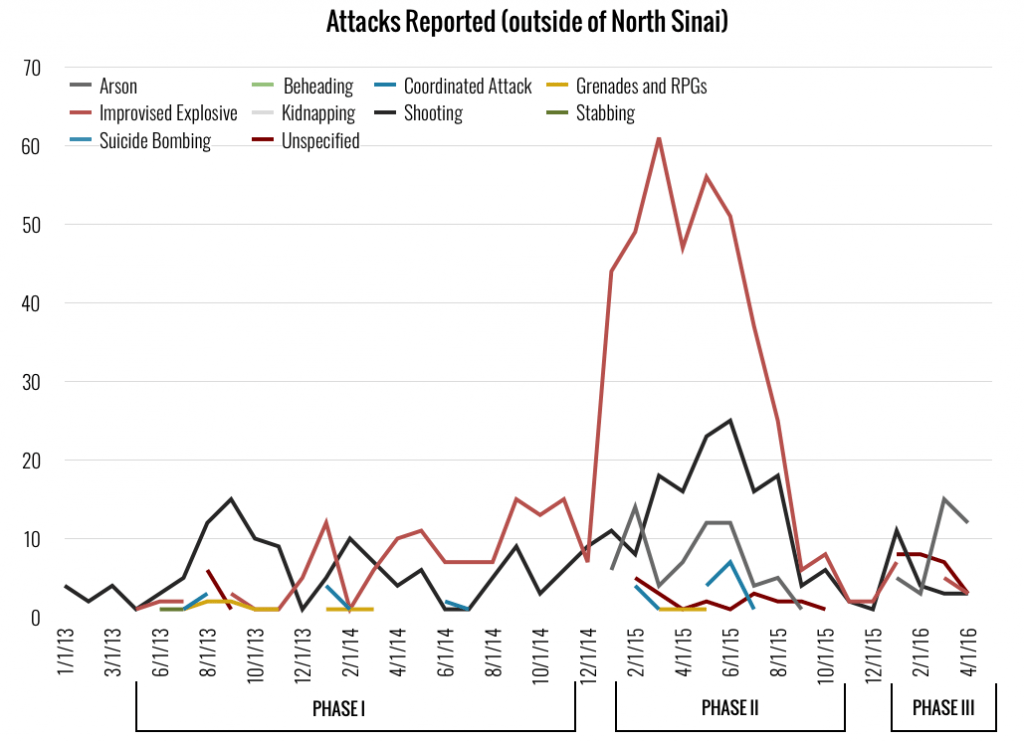

These actors are neither monolithic nor immutable; violence has seen two distinct phases, and is possibly now entering a third. While all three phases have seen a mix of small attacks with improvised explosive devices (IEDs), shootings, and intermittent large-scale attacks, the actor landscape has shifted. The first phase, following the ouster of then-President Muhammad Morsi in July 2013, featured a large number of unknown, apparently disorganized, actors carrying out attacks against security forces. The second, from late 2014 to September 2015, saw greater organization among actors, with multiple groups operating. Based on our preliminary data, it now seems that Egypt may be entering a new phase. While the contours are not fully clear, the actor landscape appears to be consolidating, with fewer unclaimed attacks and existing groups’ tactics, rhetoric, and targets increasingly similar.

Outlining the Actor Landscape

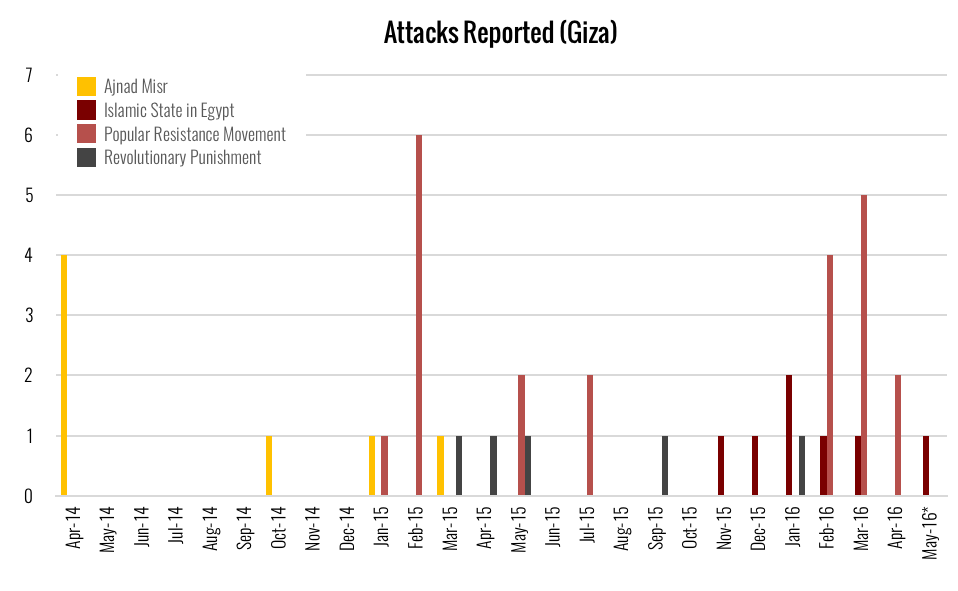

Since the first phase (and even before), takfiri-jihadist actors have been present in the mainland. Widely known for their presence in North Sinai as Islamic State “province” Wilayat Sinai, this type of actor justifies violence with religious reasoning, declaring their enemies “apostates” and worthy of death. Operating around Giza, al-Qaeda affiliate Ajnad Misr carried out 31 attacks before falling silent after the death of its leader and founder Hamam Attiya during a security operation in April 2015. The Islamic State in Egypt (again, distinct from its Sinai counterpart) later claimed attacks in the same areas in which Ajnad Misr previously operated, suggesting potential overlap between adherents.

Aside from the takfiri-jihadist activity, the large majority—84 percent—of attacks in the first phase of violence were carried out by unknown actors who mostly targeted the security sector with shootings or crude explosive devices. Morsi’s ouster outraged a large segment of Egyptian society, and, as our data indicates, in the subsequent period many resorted to violent means to redress this disenfranchisement. Across Egypt, they set cars ablaze, destroyed property symbolic of the state, assaulted police officers, and blockaded streets with makeshift barriers and burning tires. The violence was localized, where the actions of police toward families, friends, and neighbors were personal and not easily forgotten. Security forces’ unbridled handling of these individuals (often regardless of whether they were peaceful or violent) was merely fuel thrown on the fire.

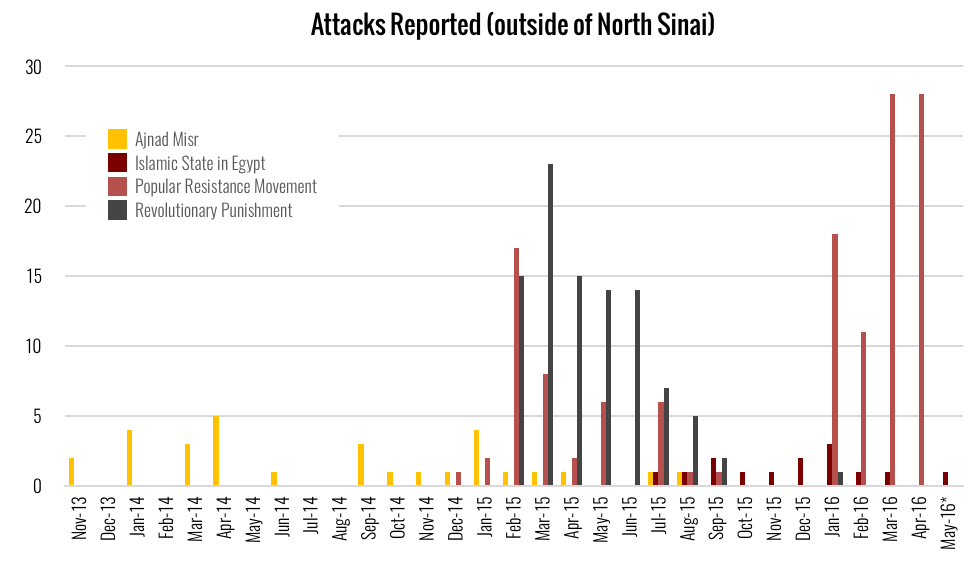

These unclaimed attacks, the near totality of which the Egyptian government attributed to the Muslim Brotherhood (although the group has denied its hand in any violence), continued (and in fact intensified) throughout 2015. But a second phase of violence began in late 2014 when an alliance of five groups announced their presence, declaring themselves the “Allied Popular Resistance Movement.” While little is known of the alliance outside of its own media, it might best be described as a grassroots organization with a central, strategy-defining nucleus that has relatively weak connections to its members. The eponymous Popular Resistance Movement and the Revolutionary Punishment were most active organizations in the alliance, carrying out 43 and 93 attacks, respectively, from December 2014 to August 2015.

In one of its first statements, the alliance referenced the “unprecedented evolution, audacity, unification, and coordination in rebel and unknown actors at all levels of the republic,” as a development promising “black days” for Egypt. Unlike the takfiri-jihadists, the group did not use religious justification for its violence, but instead employed language of continuing revolution. It also credited its emergence to the rise of new, “revolutionary” youth leadership in the Muslim Brotherhood. A Facebook page, “Below the Ashes,” promoted attacks carried out by the Popular Resistance Movement networks, featuring photos Morsi and the four-fingered Raba’a flag (commemorating the massacre in which hundreds were killed by security forces at a pro-Morsi sit in at Raba’a al-Adaweya Square in Cairo). The exact ties to the Brotherhood are unclear (and often denied by both sides), but the alliance obviously appeals to the anger and sense of injustice felt by young Muslim Brothers, who have borne the overwhelming brunt of a security crackdown—based on data collected from news and official media accounts, over 12,000 have been arrested on charges of terrorism for their alleged involvement with the Muslim Brotherhood (which has been designated a domestic terrorist organization; the Popular Resistance Movement alliance has not), even where they have not carried out any violent acts.

A Third Phase of Violence?

Now, in what seems to be a third phase of violence, the landscape seems to have transformed again. Attacks in mainland Egypt came to an abrupt standstill in August 2015, with only sporadic activity over the next few months. While the cessation of attacks may have initially been explained as the result of successful counter-terrorism activities on the part of the state, the resumption suggests that this was not the case. In this sense, the sudden and uniform halt in activity appears little less than a coordinated disengagement, which would suggest that these resistance movements had somehow been organized into a more controllable and at least somewhat more structured entity.

Perhaps more interesting, and more within the bounds of our understanding, is the change in rhetoric present in the Popular Resistance Movement’s media. Since its inception, the group has focused on two primary targets: police, especially specific individuals known for their brutality or repression at protests, and economic targets, in an attempt to weaken the state by spoiling the economy. Both of these targets have remained consistent; the group published a list of police officers’ names, with photos in February of this year, and has engaged in a more clearly defined campaign that it promotes with the Arabic hashtag “Economic Blockade.” Burning factories, destroying communications towers, and blowing up electrical pylons have all fit this objective.

But since late last year, the group has begun to use Islamic references in a way that it never had before. In December three new Facebook pages featured a new motto of “God, Martyrs, Revolution,” Quranic verses are now peppered throughout the claims of attacks, and fighters are referred to as mujahideen. The references do not appear to be accidental. Whether the result of new leadership (or media management) or a strategic decision to highlight the group’s Islamic character, there has undoubtedly been a shift. This partial Islamization of its media posts could be to appease other parties like the Islamic State, striking a middle ground between the organization’s relatively secular prospective constituents and the takfiri-jihadists.

The groups’ doctrinal transience had previously been hinted at by Revolutionary Punishment, when, on June 24, 2015, the group disseminated a video of an apparent execution-by-gunfire of an alleged police informant. Not only was this the first time the group explicitly targeted a civilian, but the publicization was new: The video mirrored those typically published by the Islamic State and featured a nasheed and Quranic verse. While this certainly does not prove any direct cooperation between the two groups, it does show that the Islamic State’s media production influences that of Revolutionary Punishment. By extension, the Islamic State could have some level of indirect influence on Revolutionary Punishment’s strategy and tactics. Indeed, in January 2016, Revolutionary Punishment and the Islamic State in Egypt both claimed the same attack in Giza, when police were lured to an apartment only to be killed by an improvised explosive.

And now, the Popular Resistance Movement also claimed the May 8 attack in Helwan; as yet, neither the Islamic State in Egypt nor Popular Resistance Movement have refuted the claim of the other. Naturally, this raises questions about coordination. The tactical character of the Islamic State in Egypt has changed since it claimed its first attack on the Italian consulate in Cairo. Last summer the group carried out a series of large-scale car bombings on key government buildings, but by November these had shifted to more targeted shootings. This could be the result of a loss in leadership, with the death of Ashraf Gharably in a security raid and the loss of figures like Hisham Ashmawy (who is believed to have worked with the group, though it is unclear when). It may also point to the carrying out of these attacks by members (or previous members) of other groups, like the aforementioned Ajnad Misr, or even by the Revolutionary Punishment or Popular Resistance Movement. Thus, in this potential third phase, it appears that the actor landscape is becoming more consolidated; whether or not they are working together, the groups are becoming more alike.

Future Implications

Despite the presence of the Islamic State, activity on the mainland remains distinctly different from the insurgency in the Sinai, which, although also rooted in local grievances, has demonstrated a high degree of centralized organization in its sophisticated attacks that the other groups have yet to achieve. Also unlike Wilayat Sinai and its predecessors, which have actively recruited and vetted members through a top-down approach, the Popular Resistance Movement has called on prospective members to form their own groups to carry out attacks and establish their commitment and trustworthiness, ostensibly as a means of evading surveillance. Facebook posts instruct their followers around the country in how to make Molotov cocktails or how to block roads effectively.

This diffusion of violence, while it may not have the same mediatized impact as larger attacks, or provoke the same knee-jerk reaction as that of the Islamic State, should nevertheless be taken seriously. As their evolution suggests, a sense of personalized and collective injustice has driven a group of independent actors to join together under the banner of violence for a cause. This makes many vulnerable to further radicalization and exploitation by groups like the Islamic State, a condition that the global organization’s leadership clearly recognizes. On May 5 and 6, 14 of the Islamic State’s “provinces” released videos in a coordinated media campaign to show the failure of peaceful political means in Egypt.

At the moment, the current regime’s unpopularity is heightened, as evidenced in recent outcry over the transfer of two islands to Saudi Arabia and large syndicate protests against police brutality. The simultaneous embrace of violence across the country suggests that should popular discontent continue to rise, it will likely not be as peaceful as in the past. The explicit targeting of security personnel also underscores that Egypt’s usual, excessively violent policing measures have and would continue to escalate the situation. While it may be too late to turn back the clock on past injustice, perhaps the evolution of violence should finally be a wakeup call that earnest security sector reform efforts with a focus on protecting human rights may indeed be key to Egypt’s security.