Summary

While sectarian violence in Egypt became of more pressing international concern after a series of deadly attacks by Egyptian militants (including those affiliated with the Islamic State), the issue is longstanding and pervasive. Sectarian violence has been perpetrated by non-state militant groups, by the state itself, and by Egyptian citizens, and harm from acts of violence has been exacerbated by a sectarian legal system, hate speech in the media, and widespread discrimination. Finally, sectarian violence in Egypt has been documented against Christians, Shi’a, nonbelievers, and Sufi worshippers, as well as against and among ethnic minorities.

Political Context

Sectarian violence has taken many shapes in Egypt and ranges from coordinated terror attacks to mob assaults. The Islamic State has claimed at least 10 terror attacks on religious minorities in Egypt, including Christians and Sufis. In November 2018, the group claimed an attack on a bus of Coptic Christians in Minya, opening fire on the pilgrims as they were traveling and killing seven and injuring 14. The attack was the first for the Islamic State on the mainland in 2018 and was reminiscent of a similar attack that took place in May 2017, when the Islamic State in Egypt militants killed 28 pilgrims in the same location. The Islamic State’s Wilayat Sinai (“Sinai Province”) also carried out a campaign of sectarian violence in North Sinai in early 2017, with multiple attacks on Christians that caused a mass exodus of the province’s Christian community. North Sinai was also the location of Egypt’s deadliest sectarian attack, when gunmen killed 305 worshippers at the mosque in the village of Rawda in November 2017. While the Islamic State had previously warned worshippers at the mosque to stop performing Sufi rituals, the attack remains unclaimed.

Sectarian violence has also taken on more spontaneous forms, often driven by local and even prosaic concerns in areas with large Christian populations, such as the province of Minya. Attempts by Christians to build, expand, or renovate churches frequently leads to local opposition, which can turn violent. On August 13, 2018, Copts in the village of Dimshaw Hashim in Minya were subjected to sectarian attacks by Muslim villagers. The attacks included chants of hostile slogans, the injury of two Copts, and damage, theft, and burning of several Copts’ houses. According to Bishop Macarius, the Coptic Orthodox archbishop of Minya, security forces had prior knowledge of the targeting of Copts by some villagers, yet they arrived four hours after the attacks. In July 2016, several Copts’ houses in Abu Yacoub in Minya were set on fire after a proposal of turning a kindergarten into a church. Inter-sectarian romances can also spark violence; in May 2016, an elderly Christian woman was dragged outside and stripped naked by Muslim villagers in al-Karm over her son’s alleged affair with a Muslim woman. Property disputes and other personal problems also have turned into communal violence between Christians and Muslims.

Some violence is both political and highly local. More than 115 attacks against churches and Christian-owned homes and businesses were documented between August 12, 2013, and August 17, 2013, in the largest wave of such attacks, which occurred around the time of the violent dispersal of pro-Muslim Brotherhood protest camps at Raba’a al-Adaweya and Nahda Squares.

The state itself has also perpetrated acts of sectarian violence, as was the case with the Maspero massacre, when security forces killed more than two dozen Christian protesters and injured at least 200 others, most of whom were Christian, when they demonstrated against the state’s failure to respond to the destruction of an Aswan church at the hands of a mob.

Other, smaller religious minorities have also borne the brunt of attacks, though these are less frequently reported, both because of the relative size of the religious minorities and because of fears of further violence. In June 2013, a mob led by Salafist sheikhs burned and attacked Shi’a houses in Giza, killing four citizens and prominent Shi’ite figure Hassan Shehata. The lynching took place after a rally led by Sunni clerics in Cairo at which they called Shi’a “heretics, infidels, oppressors, and polytheists.” In 2010, a makeshift bomb was unsuccessfully thrown at Cairo’s main synagogue. The 12 remaining synagogues in Egypt, as well as Jewish grave sites, have been left in a state of disrepair and are occasionally targets for defacement or attempted destruction.

Atheists are frequently subject to violence from family members, the public, and the state. Mainstream religious leaders (both Muslim and Christian) and state officials have claimed that the spread of atheism is a threat to Egypt and its culture. Ahmed Harqan, one of Egypt’s more outspoken atheists, was the target of an assassination attempt in Alexandria in 2014. When he reported the attack to the police, he and his wife were beaten in the police station before being arrested and charged with blasphemy. Bahá’ís are subject to discrimination and occasional violence, though incidents are not always reported.

Legal Context

Personal status laws, a discriminatory law on church construction, and numerous incidents of media incitement against minorities have contributed to a legal and institutional culture across Egypt which enables and allows sectarian violence to occur with impunity and without sufficient response from the state. Justice for victims of sectarian violence, particularly ad hoc incidents, has been rare. Authorities prefer to react to incidents of sectarian violence by emphasizing the importance of “national unity” and bringing such incidents before informal reconciliation sessions, contributing to a parallel form of justice that eats away at the standing of the traditional court system and rarely results in appropriate punishment for perpetrators or sufficient compensation for victims. In the Maspero massacre case, members of the armed forces were tried for manslaughter despite extensive documentation supporting a murder charge; they were ultimately sentenced to two to three years in prison. In the case of the December 2010 Two Saints Church bombing, the Ministry of Interior has entirely failed to file the appropriate paperwork for the case to proceed, leaving victims with little recourse nearly eight years later.

In cases involving more recent incidents of sectarian violence perpetrated by terrorists or terrorist organizations, hearings have occurred before the traditional and military court systems and punishments have tended to be more severe, as they occur in the context of the country’s “war on terror” and amid an expansive set of anti-terrorism legislation and a state of emergency. In October 2018, for example, a military court sentenced 17 defendants to death and 19 to life in prison, among others, for charges involving the targeting of two churches in 2016 and 2017 and an attack on a police checkpoint.

Trend Analysis

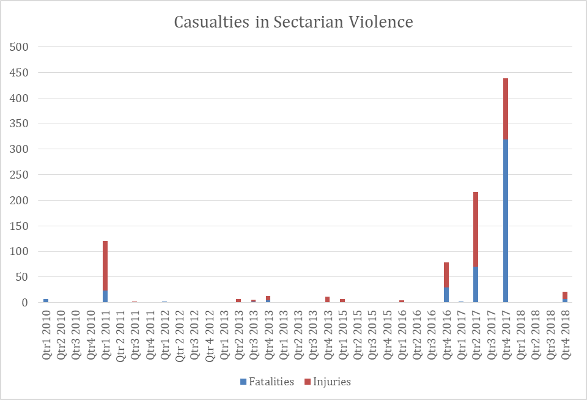

After a massive uptick in sectarian violence after late 2013, at which time over 400 incidents were reported from August 2013 to October 2015, sectarian incidents have been reported far less often, with under eight reported per month since then. Yet sectarian violence in Egypt remains a serious concern, particularly with regard to the increasing deadliness of sectarian attacks by terrorist actors such as the Islamic State: While fewer sectarian attacks have occurred in the past two years than in 2013, more civilians are being killed in them.

Implications

Sectarian violence in Egypt has caused severe physical harm and even death but also psychological and emotional trauma that harms the country’s most vulnerable populations. The state’s attempts to address sectarianism by appealing to national unity and through statements or symbolic gestures of respect for the country’s Christian population neglect the real impacts of sectarian violence on the citizens who experience the brunt of them. In addition to immediate protection for vulnerable minority groups, comprehensive efforts are needed to prevent future acts of sectarian violence. Equitable systems of justice that hold perpetrators of sectarian violence or promoters of hate speech to account; the protection of civil society organizations that support interfaith dialogue, advocate on behalf of minorities, and provide services to citizens of all faiths and none; and the reform of legal and educational systems with sectarian elements are necessary to curb and eventually halt sectarian violence.

TIMEP Coverage

“Bigger Than a Bomb: Structural Sectarianism in Egypt” (TIMEP Commentary)

“Bombing at Chapel near St. Mark’s Cathedral” (TIMEP Special Briefing)

“Killings in Arish: Rising Sectarianism in Sinai” (TIMEP Special Briefing)

“Palm Sunday Bombings” (TIMEP Special Briefing)

“Attack at Rawda Mosque” (TIMEP Special Briefing)

“Christians in Egypt” (TIMEP Brief)