On Tuesday March 7, protests broke out across Egypt in response to a rumored proposal from Egypt’s supply minister, Ali Meselhi, a Mubarak-era figure that was appointed in a cabinet reshuffle this February. Meselhi’s proposal would have effectively reduced daily subsidized bread loaves per recipient from five to three for Egyptians holding paper subsidy cards (which allow them to live in one governorate but work and purchase bread in another), as well as reduced the amount of subsidized wheat that some bakery owners could receive.

Demonstrations began in Alexandria and spread throughout the country to Giza, Kafr al-Sheikh, Minya, and Assiut, among other areas. Demonstrators in Giza clashed with police and blocked roads, others blocked rail lines, and many in Alexandria gathered in front of the Ministry of Supply office. Demonstrations in Asafra, Alexandria, were dispersed by special forces.

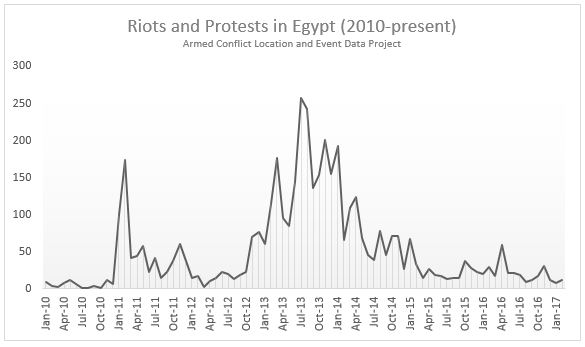

Given the complex circumstances surrounding the demonstrations—the floundering of an Egyptian economy kept afloat by a recent loan from the International Monetary Fund (and the austerity measures that come with it), intense repression of assembly by security forces and the criminalization of protest over the past years, and a history of political activity spurred by rising food prices that dates back to the Sadat era—TIMEP fellows Timothy Kaldas and Osama Diab, Mohamed Adam, and Sherif Azer weighed in on the significance of yesterday’s events:

The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP): What was the actual proposed change to the wheat subsidy scheme?

Osama Diab: Despite initial rumors of changes to individual ration cards, Meselhi decided to reduce the amount of wheat that bakery owners can get on their “Golden Cards” from enough for about three or four thousand loaves to only 500 loaves. The Golden Card is used by bakery owners to get a daily allowance of bread for citizens who do not hold functional electronic ration cards, but rather hold a paper ration card. This meant that for this group of citizens, there was a shortage of bread. It should be business as usual for those who have a functional electronic card, which is an allowance of five loaves per day per individual registered on the card. The ministry of supply claims that bakery owners have been using the Golden Card allowance system to sell some of the bread on the free market, and that this was the reason behind the reduction in their daily allowance.

Timothy Kaldas: One report from Reuters also suggested that the paper cards were used by bakers to steal part of the subsidized wheat, which is why the government has been keen to phase them out.

Mohamed Adam: This could be read as, yet again, the Egyptian state choosing not to take its responsibilities to act as a “state,” by ignoring administrative control and accounting.

TIMEP: Do the protests relate to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan? Were there safety measures in place to support vulnerable groups?

OD: The cost of making a loaf of subsidized bread has increased to 60 piasters (from around 20) after the devaluation and increase in energy prices, which was an IMF condition. Yet the loaf is still sold for five piasters, which means that for every loaf that is sold, the government pays 55 piasters in subsidies. The IMF, in its Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies, included a condition to “increase social spending on programs such as cash transfers, social pension, school meals, health insurance and free medicine for the poor, etc. by at least 25 billion” Egyptian pounds by June 30, 2017, but it remains to be seen whether this is just paying lip service due to increased pressure on the IMF for ignoring the social dimensions of its policy, or if it is a strict condition that will act as a deal-breaker on par with other IMF conditions such as value-added tax, phasing out energy subsidies, and the floating of the pound.

TK: In the IMF’s statement on the loan last November, the Fund specifically noted that the program agreed to would strengthen the social safety net by increasing funding for food subsidies and cash transfers. Therefore, any cut to food subsidies would appear to be out of sync with the plan agreed to with the IMF last fall. However, Meselhi also announced plans for a reduction in the price of rice and additional support for subsidized sugar, which suggests that the government isn’t moving to reduce food subsidies.

TIMEP: What have been the reactions from officials so far?

OD: The minister of supply seems unlikely to back down, and is implying that the owners of the bakeries were behind the riots. Also, parliamentarians vary in their position. According to media sources, some have shared Meselhi’s view that the riots were instigated by bakery owners, others have called for summoning Meselhi to question him at the parliament, and some have been trying to push him to reverse his decision.

TK: The supply minister also announced plans for a reduction in the price of rice and additional support for subsidized sugar yesterday which suggests that the government isn’t moving to reduce food subsidies. At his press conference, the minister argued that the cuts to the rations for paper subsidy cards was about eliminating waste and transitioning to a more reliable system for distributing subsidized goods.

Sherif Azer: So far the government’s response has been contradictory. The day of the riots, there was a statement denying any reduction in the bread shares per person, but yesterday the minister of supply stated that the decision is enacted, they will not withdraw it because of the riots, and that their arm won’t be twisted

TIMEP: How are security forces reacting to the riots?

MA: Different media reports suggest that the state was keen to avoid provocation, so as not to fuel the protests. However, there were also reports of arrests and of security officials threatening protesters by shooting into the air. The regime, which itself gained legitimacy via 2014 mass mobilizations that authorized it to use violence to fight “terrorism,” knew that these protesters were not politically motivated and these were the same classes of people who participated in the authorization protests. So the regime has shown that it will think twice before using the same violence typically used against politically motivated protests to disperse economically motivated protests, considering these latter probably include the same people who gave it its legitimacy three years ago.

TIMEP: Did this happen before 2011? How do today’s events compare to 1977, when protests erupted after President Anwar el-Sadat reduced subsidies on food as one of the conditions an IMF loan? Or to the 2008 bread riots?

OD: This is of course comparable (in subject if not in scale) to the 1977 bread riots, also under efforts to liberalize the economy and reduce subsidies, where many citizens protested (in many cases violently) to the point of almost becoming a full-fledged revolution. Those riots stopped short of overthrowing Sadat, due to a combination of government crackdown and a reinstatement of subsidies. Additionally, there was a massive bread crisis in 2008 that led to many deaths in “bread lines.” (It might not be a coincidence that the 2008 bread crisis happened while Ali Meselhi was Minister of Social Solidarity.) It did not lead to significant violence against the establishment, but most of the violence occurred in the bread lines over the ability to access the bread.

MA: The difference between what happened yesterday and 2008’s events that people this time directed their anger against the state instead of killing each other in the bread lines.

TIMEP: How do today’s protests and demands relate to other recent protests and mobilizations?

SA: I don’t see any relation between Monday’s riots and any ongoing movements or mobilization, as those this week were a spontaneous reaction to the decrease in the bread allotment. But, there was an online debate among January revolutionists about whether they should support those demonstrations. One side sees this a separate incident that is not related to the revolution and will not exceed the specific demands of increasing the bread allotment, and there are no general demands of reforms. The other group sees it in the core of the January revolution demands—”Bread, freedom, and social justice!”—and thus should be supported.

TIMEP: Are there any policy alternatives?

TK: Leaks and bakers skimming from subsidized supplies of flour has reportedly been a problem for quite some time. While eliminating waste from the subsidy is certainly worthwhile, the ministry should have announced these measures before implementing them, rather than two days later so that the public would understand what’s happening and to avoid scaring a group of vulnerable citizens already struggling in the face of historic levels of inflation. Once again, the government failed to communicate in a timely fashion with the public creating unnecessary uncertainty.

MA: The Egyptian state needs to stop looking for short-term and unsustainable solutions to its economic crisis; instead there should be a long-term strategy to handle the ongoing crisis and its consequences. The state also needs to urgently seek political reform to reactivate local councils and should bring back the role of civil society, currently facing an unprecedented crackdown, as a mediator between the society and the state. The ongoing economic crisis has and will continue to force the state to make decisions that directly affect people’s daily activities and it cannot afford to do so without the help of the civil society, as well as representative and transparent local representation, as channels to express grievances.