Calling a coup a coup on Facebook can lead to a 10 month jail sentence in Tunisia, as was the experience of MP Yassine Ayyari, who was convicted this February for insulting the president and the army in an online post. Describing President Kais Saied’s power grab as a “foreign-backed military coup,” Ayyari was referring to the steps that Saied took to freeze parliament and sack the prime minister in the summer of 2021.

Similarly, the arrest of lawyer Abderrazak Kilani has sparked widespread condemnation among legal professionals and public figures. Kilani was taken into custody after being interrogated in early March, following his Facebook posts criticizing the president and arrest practices in the country.

Over the past seven months, at least five similar cases involving freedom of expression have appeared before the courts with several other lawsuits against Saied’s political dissidents underway, says Emna Sammari, lawyer and member of the Tunisian Association for the Defence of Individual Liberties.

Since his election by an overwhelming majority in autumn of 2019, Saied has moved steadily towards autocratic rule and tightened his grip on rights and freedoms. One of his latest actions to this effect has been the appointment of a temporary replacement for the country’s Supreme Judicial Council, a body he dissolved last February, raising serious concerns on the independence of the judiciary. Following Saied’s steps to de facto abolish the country’s constitution and rule by decree, the judiciary had been perceived as one of the last remaining institutional checks on his actions.

Amnesty International recently reported that Tunisian military courts, controlled by Saied, have routinely tried civilians—including political activists and journalists—as part of the crackdown on dissent and free speech. Saied has intervened in judicial matters, particularly the military judicial system, leveraging his role as supreme commander of the armed forces, and therefore, overseer of all military structures and the military judiciary. The military justice code punishes with up to three years in prison “any person, military or civilian, who denigrates the flag, defames the army, or incites military personnel to disobey or criticize military leaders.”

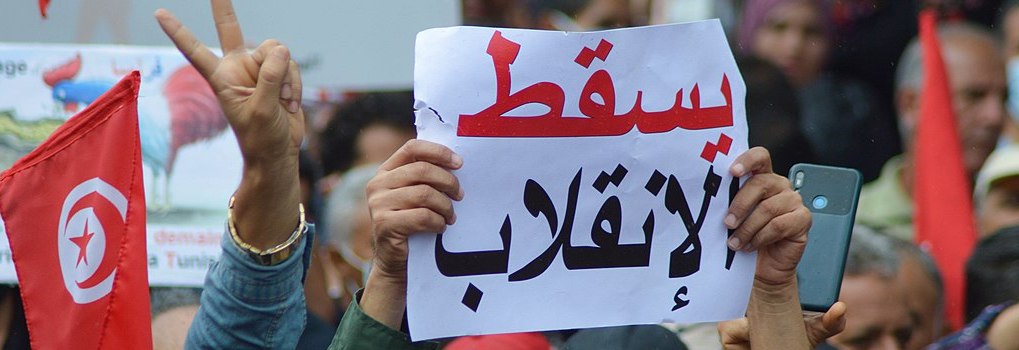

Saied has not backed away from deploying thousands of police to hinder, harass, and threaten protesters; protestors have been dispersed and besieged by police tear gas and water cannons when they have taken to the streets. The leaders of the main opposition movement, Citizens Against the Coup, have been subject to various forms of intimidation and surveillance. So far, dozens of opponents have been placed under house arrest.

As national television journalists protest against attempts to undermine editorial independence, civil society groups caution against a return of self-censorship in the media. Several national figures, including the former head of the Truth and Dignity Commission, Sihem ben Sedrine, have previously warned that most media continue to be owned by pre-revolution owners. This jeopardizes the democratic process despite important legal reforms, including the enactment of the Law on Freedom of the Press and the Law on Freedom of Broadcast Media, respectively Decree 115/2011 and Decree 116/2011.

Contrary to the actions he has taken thus far in clear violation of citizen rights, Saied intersperses his rhetoric with promises to ensure the protection of basic rights and deliver a “real” democratic system. He talks himself up as “the man of the people” to “correct the paths of the revolution and its history.” The catch-22, however, is that in order to sustain his image as the savior of democracy, Saied must protect freedom of expression, commonly perceived as the sole achievement of the 2011 revolution. But this very same principle can become his worst enemy, as it allows for dissent against him to build and to challenge the narrative that he has worked to promote.

Saied claims that the “exceptional measures” he upholds are an embodiment of the popular will, described as such in his September 2021 decree. He stipulates the supremacy of the will of the people—personified by the president—over the law and rules of institutions. In this interim period, decree-laws are not subject to appeal or annulment. Thus, the president becomes one with the state and its bodies and he further consolidates control.

Against this backdrop came Saied’s announcement of a roadmap composed of a digital consultation, a referendum, and elections; it seemingly aims to allay the fears of a premature death of Tunisia’s nascent democracy, but it does not convince. The questions in the e- referendum are at best vague, complex, and leading in their frame, as in Saied’s case, dissent would be tantamount to political suicide.

Yet, at the same time, the further he goes in suppressing freedom of expression, the greater the risk of entirely losing popular support. With time, the concept has gained a firm foothold in Tunisian society. While post-July 25 surveys paint a dark picture of how Tunisians feel about democracy, they also show that most people are not willing to relinquish political freedoms. Therefore, to safeguard his credentials as “guardian of the revolution,” Saied opts to remain seemingly tolerant toward some minor level of dissent. He limits arrests of critics mainly to individuals associated with the Ennahda party, seen by some as the main culprit of the flawed democracy prior to Saied’s seizure of power.

If Tunisians seem “okay” with this crackdown, it is because the majority has not yet felt their freedom of expression is at risk, often recalling that even before the summer of 2021, political dissidents occasionally ended up in prison as well. But Saied, as opposed to his predecessors, has carefully reduced freedom of expression to a weapon for self-preservation, while not shying away from inflammatory language.

He has granted and curtailed freedom of speech according to his political interests. When the police used tear gas and water cannons against demonstrators, Saied described it as actions taken “to protect citizens from those who abuse freedom.” When dissidents have exercised their rights to freedom of expression in opposition to him, Saied has referred to them as Tunisians who “insult and defame.” On December 22, 2021, former president Moncef Marzouki was sentenced to four years in jail on charges of “conspiring against state security”—a justification that Saied recently used to pave the way for a draft decree that would prohibit civil society groups from receiving foreign money and restrict civil society more generally.

President Saied’s discourse reveals a deep-seated aversion to institutions, which in his view are intrinsically partisan and consequently, an obstacle to the popular sovereignty. Philosophically speaking, Saied had argued in his campaign speeches, “the people are homogeneous.” There seems to be no room for pluralism in his thinking. Presumably, this is where the greatest danger for the survival of freedom of expression lies.

The September 2021 decree states that, if required, all procedures can be overruled to suit “the will of the people,” calling into question the legitimacy of procedures, mechanisms, and institutions—basic principles of the rule of law. With Saied identifying himself as the legal representative of the people, any criticism aimed at him is one that he can argue to be disrespecting the will of the people, with no recourse to independent legal arbitration.

In sum, in Tunisia, freedom of expression is no longer a right but a favor, granted and restricted according to Saied’s political interests. New attacks are to be expected as pressure mounts both domestically and internationally. But the institutions are resisting. Ten years of democratic practice proves more successful than assumed. Significantly, the slogan of those in opposition is “The people want what you don’t want.”

Faïrouz ben Salah is a Dutch-Tunisian journalist and researcher based in Tunis.