The Egyptian regime’s propaganda machine has been active in promoting the idea that Egypt is going through a phase of political openness. As part of this effort, the government held the Egyptian Family Iftar in April 2022, during which President Abdel-Fattah El Sisi announced, among other other things, the reactivation of the Presidential Pardon Committee, which had been originally formed in 2016 but whose work had been halted for years. However, numbers on the ground show a different reality. The number of arrests has increased in 2022 and so has the number of people who were subjected to illegal arbitrary practices such as renewed pretrial detention. These numbers lead us to ask ourselves two questions: how does the Egyptian regime deal with the file of political prisoners in the first place? And what is the extent of the Pardon Committee’s contribution to dealing with the ever worsening political prisoners’ file?

Since the launch of the National Human Rights Strategy in September 2021, the Egyptian regime has claimed that it has been working on improving the country’s human rights situation. During the Egyptian Family Iftar in April 2022, Sisi announced his intention to work on a national reconciliation process, and to launch a national dialogue that includes all political forces in Egypt without any exception.

A number of opposition figures were invited to that 2022 iftar. Yet, those affiliated with the Islamic movement were excluded from the invitation except for the pro-regime al-Nour Party. Among the invited was Khaled Daoud, who had previously been arrested and held in pretrial detention for about 19 months, and Esraa Abdel Fattah, who had spent nearly two years in pretrial detention. During the iftar, head of the Dignity Party and former presidential candidate Hamdeen Sabahi negotiated the release of Hossam Moanes, a member of his party, and Sisi eventually issued a decision to release Moanes later.

During the nearly two and a half years after it was formed, the committee contributed in issuing approximately 1,845 pardons.

During the iftar, Sisi announced the reactivation of the Presidential Pardon Committee, which had been formed as one of the results of the Youth Conference held in October 2016. The task of the committee was to prepare lists of political prisoners for the president to release. During the nearly two and a half years after it was formed, the committee contributed in issuing approximately 1,845 pardons. These were political prisoners, and several of them had been sentenced to life for cases related to the attack on the Kerdasa police station or the killing of a policeman in the town of Mattay, both of which took place around the time of the Rabaa massacre in 2013. For unknown reasons, the committee’s work was suspended and unofficial attempts at mediation began by member of parliament Mohamed Anwar Sadat to release political prisoners and prisoners of conscience. This remained the case until Sisi’s decision to reactivate the committee in 2022.

According to statements made by members of the Pardon Committee, the committee is considered as a mediator between the security services and detainees’ families. It has no legal powers and no criteria have been determined to select its members or decide on its work.

According to Article 74 of the Egyptian Penal Code, a pardon is defined as commuting part of, or the entirety of, a prison sentence. Legally, a pardon is only issued to final judicial rulings, not to cases that are still under investigation, to ensure that the executive power does not interfere in the work of the judiciary. However, the Pardon Committee has mediated and has been involved in the release of pretrial detainees who have no final rulings issued against them yet.

Arrest, detention, and prosecutions on political grounds

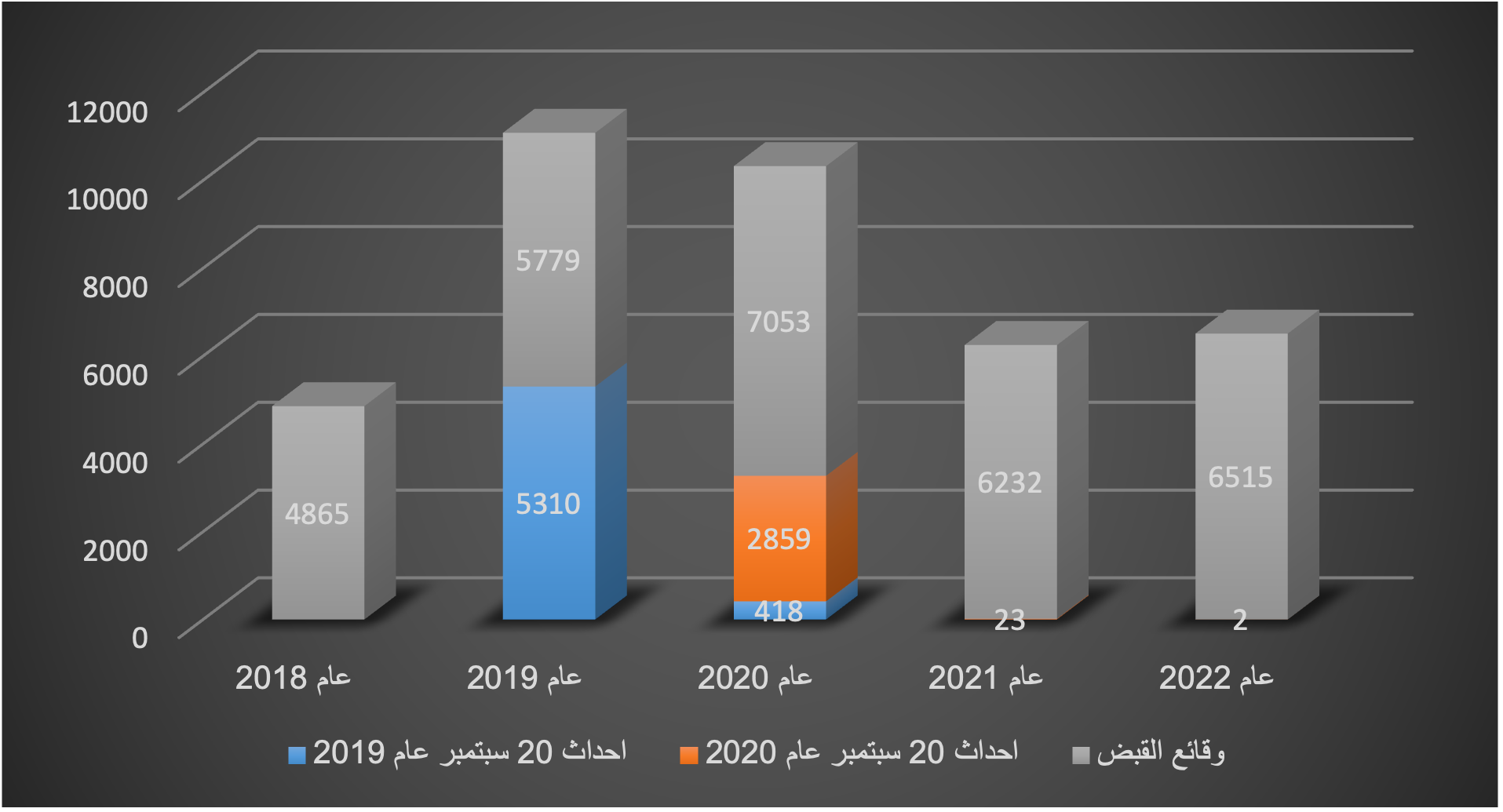

The Transparency Center for Archiving, Data Management, and Research (TADMR) has gathered all available data on political arrests and releases during the past five years, with a special focus on the years 2019 and 2020, to determine whether the presidential Pardon Committee had any role in the number of releases. The reasons behind the arrests and detentions are primarily related to demonstrations, online publishing, or joining an illegally established or terrorist group, without specifying the nature of this group. Between January 2018 and December 2022, TADMR accounted for 39,057 arrests, detentions, and security and judicial prosecutions in all of the country’s governorates except North Sinai. This is due to a complete blackout on all information and data related to the North Sinai governorate over the past 10 years as a result of the ongoing military operations against terrorist groups in the area.

There have been very few mass protests ever since the protests against the handing over of the two Red Sea islands of Tiran and Sanafir to Saudi Arabia in 2016, which ended with a series of arrests. Between 2018 and 2022, there were a few exceptions, such as the protests in September 2019 after contractor Muhammad Ali accused President Sisi of corruption, and one year later, when demonstrations broke out after the approval of the Reconciliation Law of Building Violations which threatened to demolish thousands of houses.

The numbers show that the annual rates of arrests and prosecutions are approximately the same: there are between 6,251 and 7,203 people arrested annually. It is important to note that these numbers represent only what could be documented and verified—actual numbers may be much higher. Graph 1 shows that more people were arrested in 2019 and 2020, compared to the other years. These arrests are linked to the protests in both years; security forces not only arrested protestors, but also tracked down and arrested hundreds of people who reacted to the events on social media in the following months.

In theory, and legally, the indictment stage begins after the arrest. The person arrested is subject to pretrial detention, which is regulated by law and involves specific mechanisms. However, in the past few years, pretrial detentions have been used as a form of punishment. According to the law, pretrial detention should not go beyond two years, however, people have been kept in pretrial detention for more than four years. By looking at the number of people held in pretrial detention, we found that there were 4,773 detainees held in arbitrary pretrial detention for more than the allocated two year period, 1,418 of whom were held in pretrial detention for more than four years. The actual numbers may actually be double the declared number, as the data available only refers to the cases that were documented and verified, whether through the known duration of detention or the availability of a renewal decision. Currently, there are at least 1,229 persons who are illegally detained in pretrial detention.

The Egyptian regime uses this practice to keep detainees in prison after the end of their original sentences or when no evidence is found against them, necessitating their release.

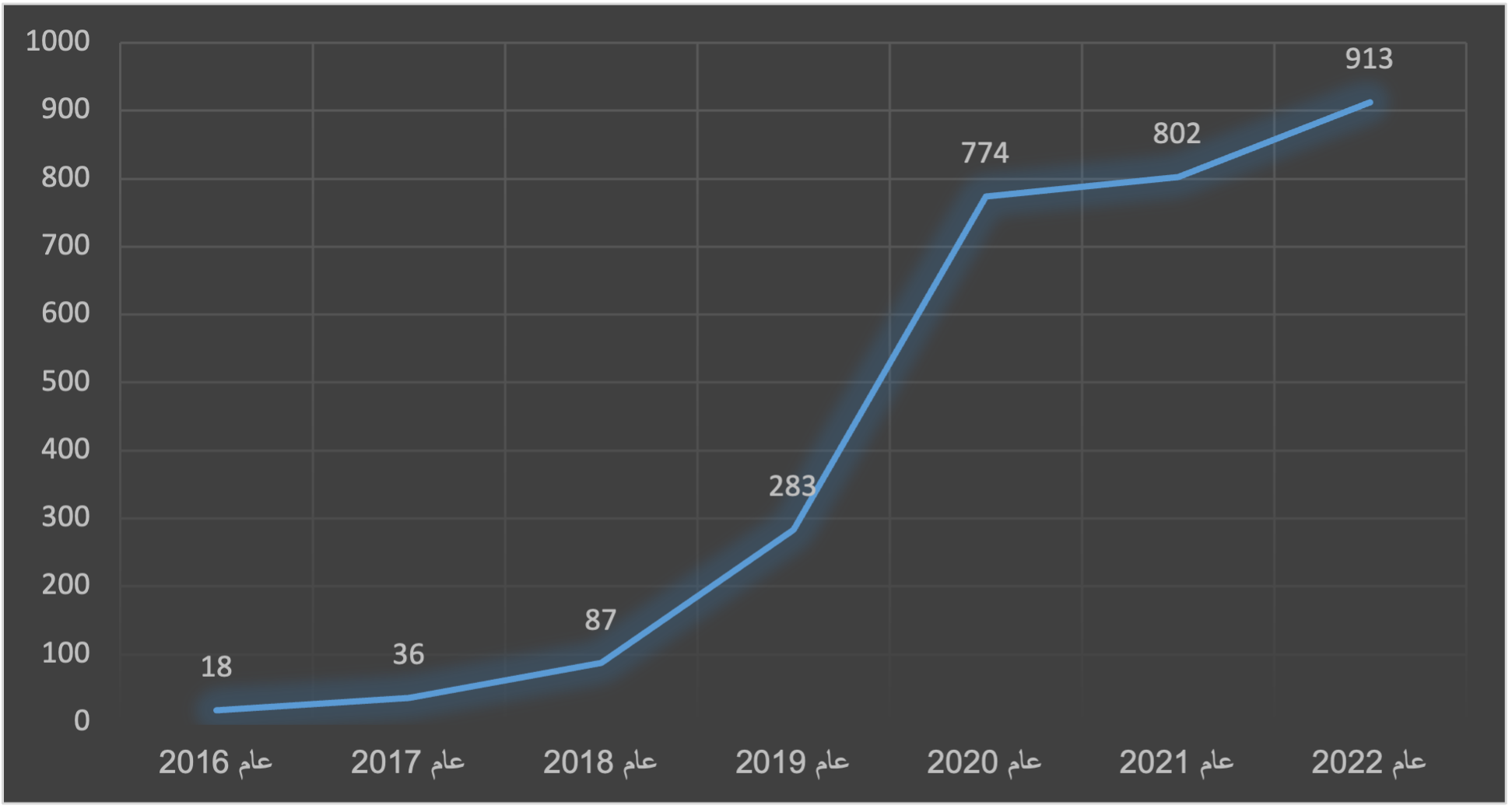

In order to circumvent the legal pretrial detention period defined by law, the regime has resorted to the practice of rotation of detainees by accusing them of new charges or re-accusing them of their initial charges. The Egyptian regime uses this practice to keep detainees in prison after the end of their original sentences or when no evidence is found against them, necessitating their release. Once new accusations are brought up against them, law enforcement can then justify keeping them in pretrial detention. The documented data indicates that the number of detainees whose detention was rotated for the first time increased exponentially, including in 2022, when the regime reinstated the Pardon Committee. Instead of ending—or even easing—this oppressive practice, the number of prisoners subjected to rotation increased in 2022 compared to previous years. In 2022, 913 cases were rotated for the first time, compared to 809 in 2021.

Graph 2 shows a general overview of the arrests, detentions, security and judicial prosecutions, and rotation cases between 2016 and 2022, including individuals sentenced and imprisoned in pretrial detention for prior periods. Despite the regime’s claims that it will work on solving the problem of detainees in pretrial detention, the number of people who have been arrested and prosecuted by the authorities, as well as victims of arbitrary practices, has increased.

The role of the Pardon Committee in releasing detainees

According to the statements made by members of the Pardon Committee, they are currently working on issuing pardons to two types of detainees: those who failed to pay their debts and those detained for political reasons. We are primarily concerned with the case of the political detainees.

Up until the reactivation of the Pardon Committee, there were two ways in which the Egyptian regime dealt with pretrial detainees: a legal one and a political one. Legally, the Supreme State Security Prosecution or the forensic crimes department would decide on releasing a number of detainees. Politically, former MP Mohamed Anwar Sadat would mediate the release of prisoners.

Even with the reactivation of the Pardon Committee, the Supreme State Security Prosecution is still entrusted with issuing a decision to release detainees. Its decision regarding the detainees’ release is implemented with or without notifying the Pardon Committee. This comes to show that the committee does not hold the ultimate power in these situations.

According to a statement made in October 2022 by lawyer Tariq Al-Awadi, a member of the Presidential Pardon Committee, approximately 1,040 pretrial detainees and 12 prisoners were released since the committee started its work. However, Al-Awadi’s statement is inaccurate because it includes all the people who were released during this period, and not those that the committee helped release. The number mentioned by Al-Awadi includes all the lists announced by the committee, in addition to all the decisions issued independently by the State Security Prosecution and the criminal departments. A closer look at the numbers reveals that only 608 people were released due to the committee’s efforts.

This confirms that the committee’s function is more informational and promotional than political, and does not help make any real changes regarding the release of larger numbers of prisoners.

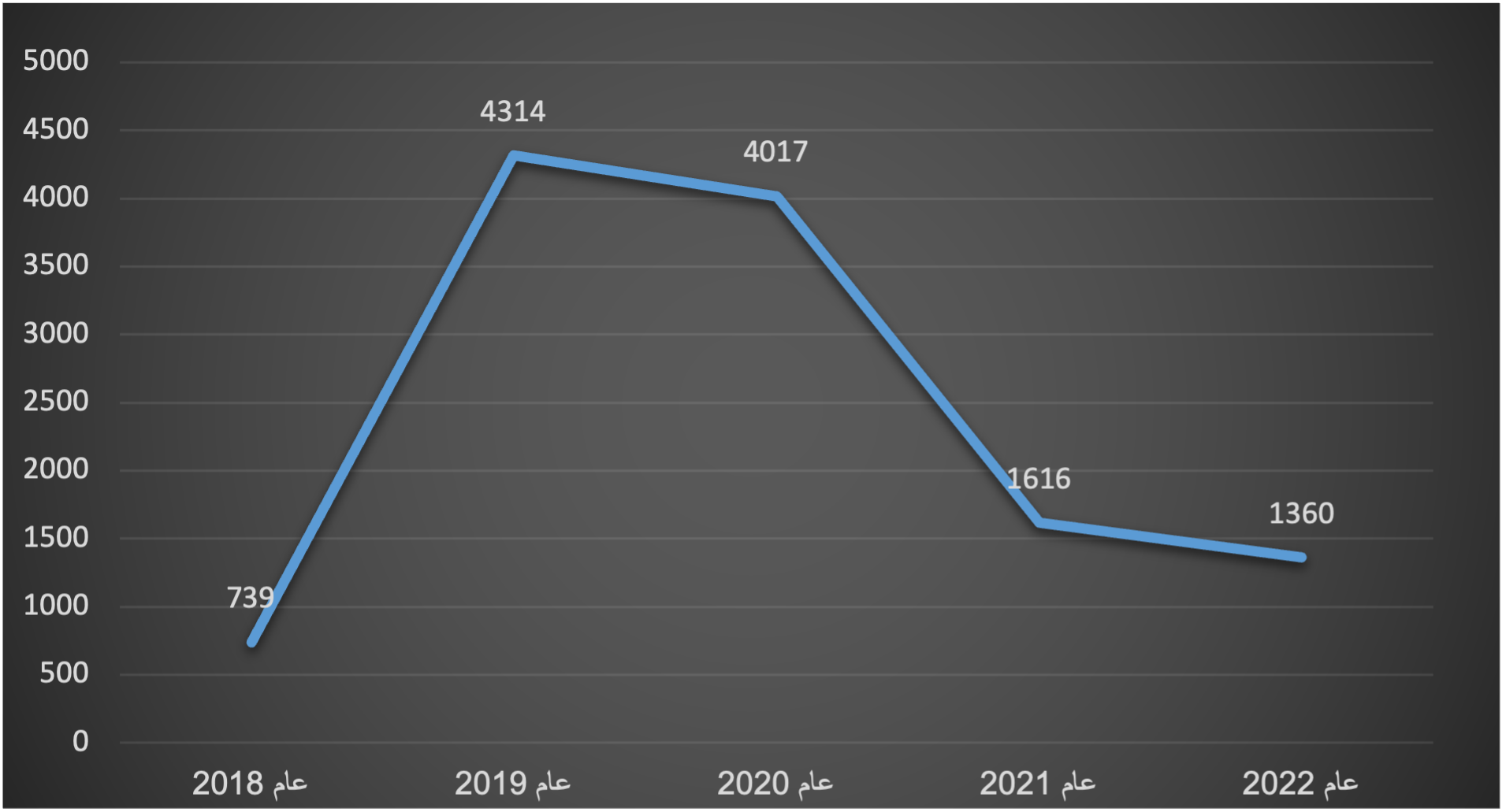

In total, 1,360 detainees were released in 2022, compared to 1,616 in 2021. In other words, there were less people released with the Pardon Committee when one would expect the opposite. And when we compare the numbers of prisoners released with the previous Pardon Committee between 2016 and 2019, we find that in May 2018 only, a presidential pardon was issued for 560 prisoners, some of whom were serving life in prison. Currently, the current committee issues sporadic lists containing a maximum of 70 names. This confirms that the committee’s function is more informational and promotional than political, and does not help make any real changes regarding the release of larger numbers of prisoners.

Graph 3 shows an increase in the number of release decisions issued in 2019 and 2020, which coincides with the high number of arrested people after the September protests in these two years. During this time, arbitrary arrests were carried out in the streets indiscriminately, as children and people who had nothing to do with the demonstrations were also arrested and deemed suspicious, only to be released later.

In general and since 2019, the number of those released has been declining annually. Based on the available data on released detainees, we found the following:

- 39 of those arrested during the protests of September 2019 were released after three years of pretrial detention, although the legally prescribed period should not exceed two years.

- 179 of those arrested after the events of September 2020 were released, the majority of them being residents and workers taken into custody while they were protesting against the construction law that was approved before these events.

- 244 of those arrested in 2022 were released. Many of them were arrested for posting content on TikTok, such as a satirical video criticizing high prices, or another showing children throwing water bags at passers-by in Port Said during Ramadan.

Despite the intense propaganda to promote a new phase of political openness in Egypt, there have been more arrests in 2022, and more people were subjected to illegal arbitrary practices. The Egyptian regime did not take any concrete steps to bring about any breakthrough in the case of political detainees, and the political and media façade was aimed at covering up the realities on the ground. That being said, such arbitrary practices eliminate any opportunity for dialogue before it even starts.

Amr Ahmed Ibrahim is an Egyptian human rights activist and founder of the Shafafya Center for Research, Archiving, and Data Management.