A number of violent actors operating inside Egypt—some jihadi and others not—seem poised to instigate a deadly Islamist insurgency the likes of which Egypt has never seen, even in the era of terror violence in the 1980s and 1990s. The case of the recently disrupted Giza-based jihadist group Ajnad Misr, or Soldiers of Egypt, is thus far the most significant indicator that the jihadist message has penetrated the Egyptian heartland. The group has carried out 16 known attacks, killing at least six police officers and a civilian since December 2013. Incipient violent groups like Ajnad Misr do not present an existential threat to the Egyptian state, which for now has the tools to play its own game of jihadist whack-a-mole on amateur difficulty. The threat a group like Ajnad Misr represents is in serving as an inspiration that may help mobilize many more Egyptian Islamists to experiment with violence. Security forces lump these different groups together out of political expediency, simply stating that they are takfiri and in some way doing the Brotherhood’s bidding. However, careful analysis of the Ajnad Misr’s rhetoric and strategy in particular indicates that these simplistic classifications may miss the mark on an emerging radical current wishing to turn Islamist anger to violent jihad.

Who Are Ajnad Misr?

Ajnad Misr’s rhetoric and police investigations offer clues about its identity. In July 2014, details released about 20 alleged Ajnad Misr members showed that members were all in their youth (average age of 26), from the Nile Valley, and some held advanced degrees (at least one Azhar educated). The group’s rhetoric offers strong evidence of a Salafist influence. Their first statement quoted from Sheikh Ibn Taymiyyah, perhaps the Salafists’ most revered scholar. An early audio recording uploaded to the internet with the group’s logo was of a young man railing against what he described as an “occupation” in reference to the Egyptian military and its “crusader” allies (Egyptian Christians and secularists) who fight Islam and destroy mosques but open “cinemas and brothels.” He went on to declare jihad and invite Egyptian youth to join him, before swearing allegiance to Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. The statement is full of grammatical mistakes and reveals difficulty to recite the Quran correctly. The allegiance to al-Zawahiri is unorthodox, amateurish, and reveals an attempt to subscribe to a global jihadist movement about which these local Egyptian actors likely know very little. (To this day, for instance, the Sinai based Anasr Bayt al-Maqdis, or ABM, has not made official if it swears allegiance to al-Zawahiri of Al-Qaeda central or al-Baghdadi of the Islamic State.) Ajnad’s rhetoric may be Salafist, and it subscribes to Salaf-jihadism, but there is no indication that it considers society and the security forces as a whole as apostates, at least not yet.

Understanding the Salafist influence is important for it highlights how this group and similar ones that may pop-up are not necessarily an extension of the Muslim Brotherhood and its ideological outlook, as the government contends. The group’s first video offers further clues about its members’ Salafist orientation. In it, they focused on a Salafist victim by the name of Sayyid Bilal who was tortured to death by security forces for his alleged role in bombing a church early 2011. More important is the use of the phrase “We will live dignified,” which is the trademark of former Salafist presidential candidate Hazem Salah Abu Ismail and his fanatical supporters. The group has also decried “man-made laws” in its official statements, which is not a common point of contention for Muslim Brothers as it is for Salafists.

What does Ajnad Misr want?

The group has a simple stated immediate objective: retribution for those killed and assaulted by security forces. In fact, the name of the group’s campaign, “Retribution is Life,” specifically revolves around revenge for Islamist victims and is derived from a verse in the Quran [2:179]: “And there is [saving of] life for you in retaliation, O men of understanding, that ye may ward off (evil).” They declare themselves to be “protectors of religion, blood, honor, and money,” in an attempt to distinguish themselves as selfless and mindful of the daily plight of those they allege to be protecting. This is only one indication of the groups’ members attempt to characterize themselves as distinctively Egyptian. The Ajnad Misr logo features two hands caressing the word “Egypt,” and a map of Egypt usually appears in the background. They have also relied heavily on social media, incredibly popular among Egyptian youth, to maximize their impact. This Egyptian character makes the group relatable and to its target audience of Islamists less problematic than the crass takfirism of ABM and similar groups.

The reliance on social media and the careful development of an ostensibly Egyptian character allows the group to attract sympathy and support, particularly among young Egyptians. It directly exploits the main catalyst of Islamist anger following Morsi’s ouster, the August 2013 massacres at the Raba’a and Nahda sit-ins. The latter was in Giza, and, according to investigations, some of the Ajnad suspects were themselves protesters in Nahda Square. At least two of the officers assassinated by the group were allegedly directly responsible for the clearing of Nahda Square.

Besides claiming to avenge the deaths of those killed in Raba’a and Nahda, the group has also kept its rhetoric updated with the latest sources of anger in the Islamist street, namely the alleged rape and sexual abuse of female Islamist detainees. The narrow focus on retaliation and exploiting popular anger toward sexual abuse makes the group’s rhetoric accessible and acts as a “gateway” to potential recruits who may otherwise not have been attracted to the jihadist message. Ajnad Misr’s objectives are beyond this narrow focus of retaliation, however. In its founding statement the group claims to be fighting for the establishment of a religious state in Egypt and in typical Salafi jihadist fashion states its desire to free people from “enslavement to anything other than Allah,” and to kill the soldiers of at-taghut, or what is worshiped other than Allah (idolatry).

Calculated Violence against Security Forces

In its eight months of activity, the group implemented increasingly daring and deadlier attacks using improvised explosive devices (IEDs) to target police. They were careful not to target civilians, killing only one by accident using a car bomb, reportedly confusing his for an officer’s car. This indicates that the expertise for sophisticated IEDs is accessible to other actors who may become inspired by the group. For its ability to kill senior level officers and carry out operations for such a stretch of time the group has exposed weaknesses in the state security apparatus after eluding it for months.

Ajnad Misr made its first public debut on January 24, 2014, when it issued a statement claiming responsibility for two attacks in Greater Cairo; these smaller attacks occurred in the shadow of ABM’s attack against the headquarters of Cairo’s security directorate that left six dead and over 70 injured. The multiple attacks on that day across the Cairo metropolitan area had a tremendous psychological impact on residents, many of whom were left feeling that their city was under siege and that terrorists had gained an upper hand. Even with these feelings of insecurity, many doubted the authenticity of a previously-unknown group’s claim to the attacks. Ironically, what confirmed to skeptics Ajnad Misr’s claims is when the group crossed wires with ABM over responsibility for the smaller attacks, which targeted police in Giza and killed two. ABM, which had issued a statement claiming responsibility for all violence that day, later ceded credit to Ajnad Misr for their claimed attacks. This recognition from an established terrorist group proved for many Ajnad Misr’s credibility.

In the same late January statement, Ajnad Misr took responsibility for three earlier bomb attacks in Cairo that were heretofore unclaimed. According to the statement, the attacks were carried out to test the response of security forces and look for gaps to exploit.

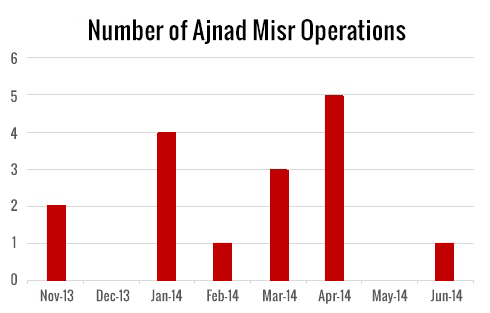

Since January 2014, the group has carried out eleven more attacks specifically targeting police forces (Figure 1). They usually plant homemade improvised explosive devices (IEDs) near police targets, indicating their ability to do reconnaissance and clandestinely breach patrolled areas. The most significant of these endeavors was the latest attack outside the Ittihadeya presidential palace. Daringly, the group released a statement revealing to police where to find the bombs; the explosives were triggered when police attempted to diffuse them three days later, and two officers were killed.

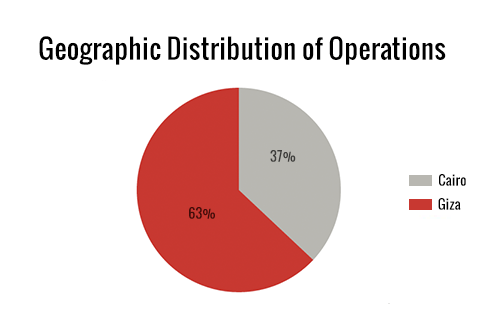

The geographic distribution of Ajnad Misr’s attacks shows that the base of operations is in Giza governorate where 63% of the attacks have been carried out thus far (Figure 2). The remainder has been in Cairo governorate, with one attack targeting a camp on the Cairo-Alexandria desert highway. The group used firearms in only one attack against a police traffic post on January 7, 2014, but this resulted in no fatalities. In every other attack, the group has used IEDs, revealing an instantly identifiable modus operandi after only a few months of activity. Based on its statements and claimed attacks, the group has thus far avoided killing any civilians and goes out of its way to claim that this is its utmost priority. It claimed, for instance, that throughout the month of March 2014, its attacks resulted in no injuries due to the use of a lesser amount of explosive material. It has also claimed to cancel many attacks due to the possibility of civilian injury or loss of life.

The specific targeting of police officers is a tactic adopted by other violent actors currently operating in Egypt. This is due to the belief that the police are the “weakest link” in Egypt’s security apparatus. Violent actors thus wish to overwhelm it with attacks that may yield the same result as in January 28, 2011, when the police force across Egypt was paralyzed after only one day of sustained protests and attacks on police stations.

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/1″][intense_promo_box shadow=”0″]Information compiled from Ajnad Misr official statements and news sources. March 2014 attacks have had minimal to negligible results per the group’s own admission. The group has claimed 16 total attacks, however, preliminary investigations reveal that the prosecution has only charged them with 13. Ajnad Misr attacks have resulted in the deaths of six security service members and one civilian, according to the prosecution.[/intense_promo_box][vc_column_text]

The Syrian Connection?

In a videotaped, pre-rehearsed confession, an alleged member of the group claimed that he received money from Muslim Brotherhood supporter, Wagdy Ghoneim, formerly based in Qatar. The suspect, aged 24, allegedly traveled to fight with the Salafi Ahrar al-Sham in Syria and linked up with other young Egyptian jihadists influenced by the jihad in Syria. The confession is most likely the result of torture and to satisfy the authorities’ desire for a smoking-gun connection to the Brotherhood. However, it should not distract from the fact that many Egyptians have traveled to fight in Syria (estimated in the thousands). A source close to the group confirmed that some members in the group;most importantly, those with whom they have been in contact had allegedly traveled to fight in Syria in the past.

The investigations detail how at least one alleged member has had tendencies in the past to join Al-Qaeda. In July 2014, one of the suspected Ajnad Misr members indicated that he traveled to Yemen in February 2012 hoping to join al-Qaeda, but Yemeni authorities turned him away. As indicated, some observers in Egypt claim that members from Ajnad Misr have indeed either traveled to Syria, or at least crossed paths with those who have; there does seem to be some visible connection, however vague and circumstantial as the claim may be. A jihadist group formerly affiliated with Jabhat al-Nusra, called Jaish Muhammad, inexplicably released a well-edited video giving Ajnad’s Ittihadeya attack the typical jihadist look and treatment. Ajnad responded to the shout-out on Twitter and thanked the “brothers” wishing victory and unity for the jihadists in Syria.

Implications for Egypt’s security

With the recent rounds of arrests, the authorities may have finally been able to rein in the group and dismantle its networks. However, the group may still serve as an inspiration for similar groups. The significance of Ajnad Misr will continue, as it was the first jihadist group based in Greater Cairo in the past decade. Its ability to carry out attacks and even taunt the police before an operation near a presidential palace confirms to those who may be considering a turn to violence that it is an attainable option. Although there is no clear evidence that the Muslim Brotherhood has founded a homegrown jihadist group like Ajnad Misr, the Brotherhood’s followers and others who sympathize with the Brotherhood could become susceptible to joining jihadist outfits due to the promise of retaliation against the police.

Ajnad Misr symbolizes the transformation of some Egyptian Salafists and their adoption of a jihadist message. There are other groups present in Egypt operating with the same objectives of Ajnad Misr in targeting the police, which they justify as retaliation for their abuses. Some include names like Execution Movement, Walaa (Set Fire), or Molotov. However, unlike Ajnad Misr, these other groups have thus far remained non-jihadi in their rhetoric, referencing their desire to enact revenge without evoking specifically religious objectives. Recently, these groups have showed a marked escalation in their tactics as anti-government activity, jihadist and non-jihadist, has increased in violence and daringness. Ajnad Misr’s track record relative to these other groups threatens to make their method and ideology an attractive alternative to the non-violent jihadi path and, of course, the largely non-violent Islamist protest movement. Ajnad’s experience in carrying out such largely-publicized attacks, even if the authorities ultimately eliminate it, may help galvanize a homegrown jihadi current that, due to its connection to the Egyptian heartland and tapping into the shared grievances of the broader Islamist current, could prove far deadlier in the future than groups like ABM ever dreamed to be.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]