While increasing access to the internet aims to pave the way for a more equitable and inclusive world, the weaponization of the internet and other technologies against women has grown commonplace. The internet and social media together have become a new frontline for violence against women and girls, and this phenomenon has increased exponentially during COVID-19 and related lockdowns. More and more, texting, email, Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube, and just about any other internet, social media, and messaging platform are being used to perpetrate violence against women.

Cyber violence against women takes many forms, including cyber harassment, cyberstalking, defamation, non-consensual pornography, hate speech, cyber hacking, and public shaming. The number and diversity of perpetrators are also increasing. For example, blackmailers are capitalizing on honey traps, private images and videos are being hacked, and cyber scammers are making fake profiles on various social media platforms, dating sites, and messaging apps to lure potential victims.

The Phenomenon and the Impact

Committing cyber violence is becoming easier for a variety of different reasons. The anonymity that can be maintained online translates into protection for those who engage in cyber violence. Wide access to basic technology means that tracking a woman’s movements or publishing defamatory remarks about her requires little technical skills. The affordability of technology makes it inexpensive to distribute a woman’s photograph or create and propagate misogynistic images and writing. The ability to contact anyone in the world from anywhere in the world broadens the pool of potential victims, expands the harm, and reduces the possibility of getting caught.

Like offline violence, cyber violence perpetuates negative psychological, social, and reproductive health impacts on victims, sometimes leading to offline physical and sexual violence as well. Additionally, it has a significant economic impact, placing a stress on financial resources. Furthermore, cyber violence is often used to preserve men’s control over women and perpetuate patriarchal norms, roles, and structures.

Social Context in Egypt

In Egypt, women have been among the most vulnerable targets for cyber violence considering existing social stigmas involving women’s personal lives. This same social stigma makes it so that when women are subject to cyber violence, they are often unable or unwilling to report these crimes or make official complaints to build cases, in effect magnifying the harm. Several victims fear the impact to their reputation when they go public, contributing to a climate of intimidation and self-censorship.

Research indicates that the most common medium for cyber violence in Egypt has been social media platforms. In one study of 356 Egyptian females, about 41.6 percent of participants had experienced cyber violence in the last year and 45.3 percent reported multiple incidents of exposure. Over 92 percent of the victims reported that their abusers were strangers, and over 41 percent of cyber harassment came in the form of unwelcome explicit images. More than three quarters of the victims experienced psychological effects in the form of anger, worry, and fear; 13.6 percent faced social harm; 4.1 percent were subject to physical harm; and 2 percent reported financial losses. Although more in-depth and extensive research and data collection is necessary to better understand cyber violence in Egypt, these early and limited findings point to a significant issue that deserves much greater attention.

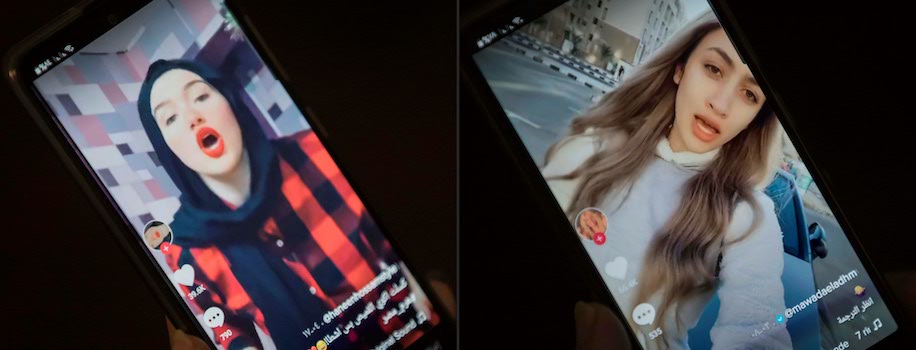

In Egypt, digital platforms have facilitated two forms of monitoring and surveillance that target women and compound the harm of cyber violence: official monitoring and more subtle familial and social surveillance. In terms of the former, there have been several instances where states have policed female-created content on digital platforms, even detaining female creators.

In the cases in which women do come forward following incidents of cyber violence, they have often been revictimized by social media and blamed for their sexual assaults through high-profile stories in the press. The case of Menna Abd el Aziz, who was gang raped by her friends, is one such example. After she went viral for posting a video crying and speaking about her rape, she was subject to a barrage of disturbing misogynistic and violent comments. The perpetrators capitalized on this toxic environment by posting photos and videos of her on the internet.

In recent months, the extent of the real-world harm of cyber violence in Egypt has been made clear. One Egyptian woman committed suicide after her husband threatened to share intimate pictures and videos online as a form of revenge. In a separate case in Gharbia Governorate, Basant Khaled committed suicide after being blackmailed by two young men who hacked her mobile phone, obtained pictures of her, altered the photos, and republished them. In yet a different case in upper Egypt’s Sharkia Governorate, Heidi Shehata also committed suicide after her neighbors fabricated her pictures and blackmailed her for money. In March 2022, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi made reference to two of these incidents in remarks about women in Egyptian society.

The Law

In August 2018, al-Sisi ratified Law No. 175 of 2018, the Anti-Cyber and Information Technology Crimes Law, popularly known as the Cybercrime Law. Several articles of the Cybercrime Law, including articles 14, 15, and 16 set forth punishments for the hacking of private accounts, the interception of content, and other related crimes. Articles 24 and 25 criminalize the creation of fake accounts and the sharing of content infringing on the privacy of persons, among other things. The law does not explicitly mention many of the forms of cyber violence faced disproportionately by women.

Considering its vague construction, implementing this law toward the protection of women on the ground has been problematic amid the labyrinth of legal procedures and an absence of sufficient will to prosecute primarily male perpetrators. A patriarchal culture in police stations often leads to shaming the victims and at times, holding them responsible for the crime they endured. The lengthy time between the filing of a formal complaint if a victim opts to do so and the initiation of an investigation allows the blackmailer to move forward with his threat and continue to perpetrate harm.

In an alarming window into state priorities, the Cybercrime Law has been weaponized to target women influencers on social media for harm to public morality, which has left them vulnerable to prosecution, and societal targeting and cyber violence of various forms.

Looking Ahead and Recommendations

Despite the distressing incidents of cyber violence against women, it is important to note that women have also used digital platforms to regain agency over issues that impact them, including violence. While the anonymity of Instagram, Twitter, and other online platforms has its drawbacks, it also offers women a safer platform for digital organizing. Women have been able to use these platforms to raise awareness about sexual and gender-based violence. For example, the Instagram account Assault Police documents and shares experiences of sexual assault and intimate partner violence in Egypt while also providing a safe area for survivors to connect. Qawem, a Facebook page and community dedicated to assisting cyber-blackmailing victims, has over 250 volunteers who run the group, respond to victims’ messages, and collect information about perpetrators.

Efforts to organize and create a space for female voices online demonstrates that digital platforms have the potential to empower women in Egypt in the face of cyber violence. This potential, however, will not be realized entirely unless social media companies take more responsibility to prevent harassment, threats, intimidation, and the incitement of violence.

Cyber violence against women must also be recognized as a form of gender-based violence in policy discussions. Egyptian legislators should amend the country’s legal framework to explicitly recognize the occurrence of cyber violence, noting its disproportionate impact on women, and to criminalize it accordingly.

The voices of women who have been victims of cyber violence must be included in strategies to combat the epidemic. Further, authorities should ensure that victims of cyber violence have access to justice and specialized support services. Finally, improving gender-disaggregated statistics on the prevalence and harms of cyber violence against women at the country level and developing indicators to monitor the effectiveness of interventions should be a top focus to allow decision makers to properly understand the extent of this crisis and develop a clear and effective plan for how to respond to it.

Habiba Abdelaal is a former Nonresident Fellow at TIMEP focusing on sexual and gender-based violence in Egypt.