Sudan experienced long political stagnation after the military launched a coup d’état in October 2021, but some political developments have recently taken place. The key development was the signing of the political framework agreement in December 2022, the first step of a two-phase political process. While this agreement has succeeded in breaking the post-coup political stalemate, it failed in building popular support.

On the back of the framework agreement, the final political process was kicked off in January, with the aim of discussing and reaching consensus on outstanding issues such as the dismantling of the former regime, security sector reform, transitional justice, reviewing the Juba Peace Agreement (JPA), and peace in Eastern Sudan. These discussions, however, are being conducted amongst signatories of the December framework agreement only; the vast grassroots movement is not represented and not showing any interest in the ongoing process as a whole. Furthermore, most of the armed movements that signed the JPA and some political parties have contested the process. Yet, the political process seems to be going forward, despite its challenges and limitations. Leaving these issues unresolved will risk ending up with a fragile final agreement that lacks support from the most influential pro-democracy groups.

Phase I: The December Framework Agreement

On December 5, 2022, a political framework agreement was signed between civilian actors and the coup’s de facto authorities. The agreement came after over 13 months of indirect and direct talks. On paper, the framework agreement has achieved great breakthroughs, particularly around stating that Sudan’s prospective transitional government will be fully civilian on all levels and will end the military’s formal role in politics. The agreement’s provisions have also emphasized establishing one professional army and other reforms to the security sectors. The agreement was signed by 40 actors, representing political parties, professional associations, trade unions, civil society, armed movements, and the Sudanese military. The agreement was amply welcomed by the international community and was even hailed by the United Nations Secretary-General.

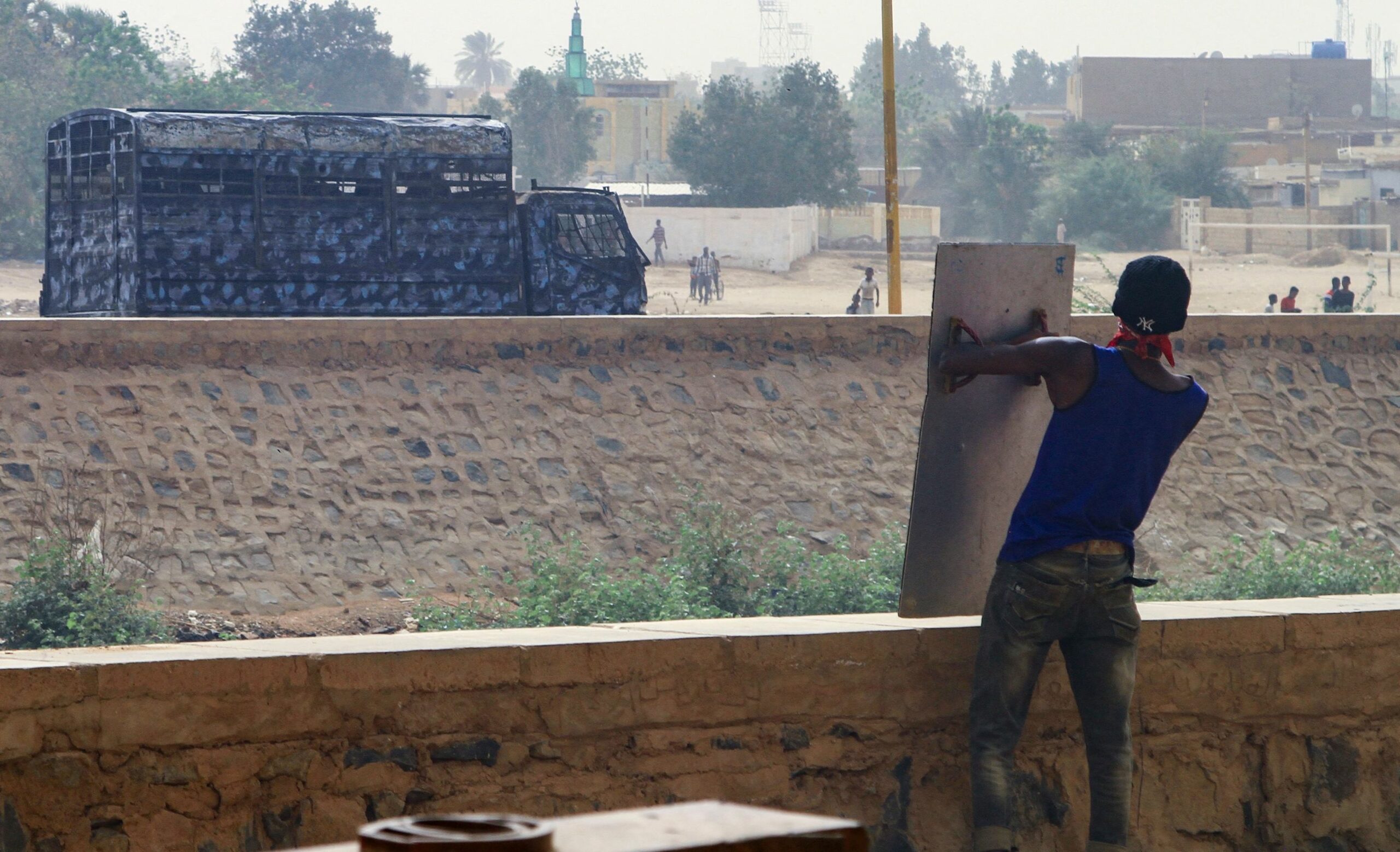

However, the resistance committees have boycotted the process and have been taking to the streets in protest of the agreement. Evidently, the resistance committees have the upper hand in mobilizing the population, hence their rejection of the agreement has extremely affected its popular support. The main concern of the resistance committees is that the framework agreement had offered the coup leaders seats on the table and could potentially guarantee them amnesty and compromise justice. Another concern is that the military and security forces made no efforts to halt their violent crackdown on demonstrations or sham trials of protesters after signing the framework agreement. Above all, those opposing the agreement do not trust the military to honor their pledge to step down from power. They feel that the framework does not offer anything different from the 2019 power-sharing agreement, which the military has essentially turned against when they launched the October coup.

Phase II: The Final Political Process

Following the signature of the framework agreement, the final political process started on January 8, 2023. The main objective of this process is to conduct workshops on sticky issues that were not fully agreed upon in the framework agreement and to build broader support for the deal. The workshops are being brokered by the Trilateral Mechanism of the United Nations, the African Union, and the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and are attended by the framework agreement signatories and other stakeholders relevant to the topics of the workshops. The recommendations coming out of the workshop should feed into the final agreement and develop wider consensus around the agreement. The contentious issues being discussed are the dismantling of the former regime of Omar al-Bashir, the Juba Peace Agreement, Eastern Sudan’s crisis, transitional justice, and security sector reform. So far, the workshops on dismantling the former regime, reviewing the Juba Peace Agreement and Eastern Sudan’s crisis were concluded and the final recommendations were published. The workshops have generally succeeded in bringing diverse voices from across the political, professional, ethnic, tribal and social spectrums. However, the way the process proceeds and ends, in terms of including more actors in the discussions, will likely play a crucial role in determining the agreement’s viability.

Despite his continuous assurances about commitment to the framework agreement, Sudan’s junta leader General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan stated that politicians should refrain from interfering in the military reform process.

The series of workshops on transitional justice has just started. The final workshop on security sector reform is expected to take place afterwards. Nevertheless, the security sector reform workshop is highly contentious, as it directly challenges the military leaders. Despite his continuous assurances about commitment to the framework agreement, Sudan’s junta leader General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan stated that politicians should refrain from interfering in the military reform process. He also said that the army does not want to proceed with the framework agreement with one side, referring to the Forces for Freedom and Change’s Central Committee, which suggests that the military is keen on having pro-coup actors in the room. Furthermore, another Sudanese army general cast doubts on the capacity of the framework agreement to end the political crisis, saying the signatories did not constitute a sufficient majority to solve the country’s problems. Hence, it appears that the reservations of those rejecting the process on the seriousness of the military are legitimate.

The parallel Cairo Process

In parallel to the ongoing final political process, Egypt proposed an inter-Sudanese dialogue process to be held in Cairo, in order to reach a quick political settlement by including the non-signatories to the framework agreement and get them to become part of the final agreement. However, the Egyptian initiative was rejected by most of the pro-democracy actors, including the Forces of Freedom and Change’s Central Committee. It was described as an attempt by the Egyptian regime to hijack the current political process in Khartoum and to obstruct the process of restoring Sudan’s democratic transition, by providing a platform that is dominated by counter-revolutionary forces.

Participants of the Cairo dialogue were drawn from various groups representing political parties and armed movements, who are known to have been in support of the military coup or have been associated with the previous regime of Bashir. At the end of the Cairo dialogue, participants had signed a “Political Accordance Document” setting out the conditions for the upcoming transitional period from their perspective. Although the military did not join the dialogue in Cairo, they had various allies in the room. Also, it was noticeable that the statements made by the military leaders suggesting a reversal from the framework agreement coincided with the dialogue taking place in Cairo. In addition to the doubts about the Cairo dialogue by Sudanese actors, high-level representatives from the US, France, Norway, the UK, Germany, and the European Union conducted a joint visit to Khartoum in February and issued a statement that strongly discouraged parallel processes, in reference to the Cairo dialogue.

Reactions to the final political process: Apathy and worries of a repeating cycle

On paper, the framework agreement responds to most of the anti-coup actors’ demands. Furthermore, the ongoing final political process has been open to a wide range of stakeholders and a Facebook page has been created to live-stream all sessions and publish the agenda and recommendations. Yet, most resistance committees continue to reject the process and the Sudanese public is showing utter apathy toward it.

Resistance committees in particular view the process as a repeating cycle of elitist political settlements that do not address the root causes of the Sudanese crisis.

Perhaps the biggest and most legitimate concern about the ongoing political process has to do with the process rather than the substance. Many anti-coup groups have criticisms about how the process started as exclusive and non-transparent negotiations between the Forces of Freedom and Change and the military leaders. Although the process was opened up to more stakeholders at a later stage, serious doubts were already building up. These doubts are being expressed through public demonstrations, as well as a lack of interest in following the developments of the process. Resistance committees in particular view the process as a repeating cycle of elitist political settlements that do not address the root causes of the Sudanese crisis. Furthermore, the continuous resistance movement since the coup took place in October 2021 and the lack of consensus on the way forward has taken a toll on the Sudanese people, particularly in the face of multi-faceted crises facing the country. Nevertheless, the hopes of restoring Sudan’s democratic transition are still high, and the ongoing political process offers a great platform if all legitimate concerns were seriously considered.

The way forward

Certainly, the power to mobilize people in the streets of Sudan rests principally with the resistance committees. Hence the legitimacy of pro-democracy civilian groups engaged in the process is essentially derived from the resistance committees. It is extremely dangerous to go ahead with a political process that lacks popular support. This will only result in a fragile agreement that will neither bring about stability nor protect the country from possible coups in the future. Whilst it is vital to have the international community’s support, pro-democracy groups engaged in the process should be careful of how much they rely on international, as opposed to domestic, support. The leaders of these groups should urgently seek new and persistent approaches to find common grounds with other pro-democracy groups, particularly the resistance committees and civil society organizations such as professional associations, labor unions, and women’s groups that were core to the original revolutionary alliance that toppled down the Bashir regime. It is also critical to increase the engagement of actors outside Khartoum, particularly in rural and conflict-affected areas. It might be hard to get all of them onboard, but it is vital to get as much support as possible from revolutionary forces.

The international community has a crucial role to play in holding the leaders of Sudan’s military to account and to take the doubts about the military’s commitment to the process more seriously.

The international community is eager to put an end to the political crisis in Sudan and restore the country’s democratic transition as quickly as possible. However, they should give Sudanese actors the time and space needed to find a unified and legitimate approach forward, in spite of the urgency imposed by the country’s crises. Furthermore, they should continue to monitor the geopolitics of Sudan’s crisis, and make every possible effort to halt the anti-democracy agenda pushed by governments in the region. Moreover, the international community has an important role to play in advocating for inclusive and transparent approaches that would offer platforms for a wider group of pro-democracy actors. Lastly, the international community has a crucial role to play in holding the leaders of Sudan’s military to account and to take the doubts about the military’s commitment to the process more seriously.

While critics of the final political process have valid and legitimate concerns, it appears to be the only game in town at the moment, presenting the sole available path to re-establish Sudan’s democratic transition. In the face of the country’s deepening economic, security, and humanitarian challenges, pro-democracy critics should aim to engage in the political process and bring their concerns and doubts to the table. It is clear that protesting the process from the outside has not resulted in any tangible changes, so it might be more sensible to try to influence it from the inside. In particular, Phase II of the process provides an opportunity for actors like the resistance committees to engage in the process without compromising their legitimate refusal to directly engage with the military. It is high time for all pro-democracy actors to double their efforts to find a common ground and agree on a path forward that has broader public support, taking into account Sudan’s rapid slide toward deeper economic and political collapse.

Hamid Khalafallah is a Nonresident Fellow at TIMEP focusing on inclusive governance and mobilization in Sudan.