Summary: Following parliamentary approval of a broad package of constitutional amendments that expand the authority of the executive branch and military at the expense of the independence of the judicial and legislative branches, Egyptians voted on the amendments in a national referendum. On April 23, the National Elections Authority (NEA) announced that 88.8 percent of voters had voted in favor of the amendments and that 11.1 percent had opposed, with turnout of 44 percent. The amendments, which significantly impact Egypt’s political future, had been hastily advanced to a national referendum in which Egyptians lacked appropriate time to consider the substance of the vote, movements and individuals critical of the amendments had been disenfranchised, and authorities had engaged in coercive and illegal practices.

Political Context: The referendum took place following two months of parliamentary review, culminating in the House of Representatives passing the amendments on April 16. While the political process was ongoing, the state had blocked websites critical of the amendments and the accompanying process, arrested citizens for publicly expressing opposition to the amendments or for criticizing the government’s performance, and subjected legislators who expressed disapproval of the initiative to smear campaigns. In an attempt to raise voter turnout, the NEA announced prior to the referendum that non-participation would result in a fine of 500 Egyptian pounds (LE). In addition to the coercion and repression ahead of the vote, the referendum dates—April 19–21 for expatriates and April 20–22 for domestic voters—gave Egyptian expatriates less than 72 hours and Egyptians inside the country less than 96 hours to review the substance of the amendments package after its passage by the House. Polling abroad was limited to 140 locations worldwide and individuals were required to vote in person.

Once the referendum was underway, multiple media outlets and journalists reported illegal vote-buying by state-aligned entities. Some citizens were promised a combination of up to LE50, food supplies, or both in exchange for their support of the amendments. At times, this occurred even in plain view of polling centers. Opposition voices continued to be silenced during the referendum, as a young man named Ahmed Badawi, was arrested in Fifth Settlement neighborhood of Cairo on April 21 for holding up a sign in a public space opposing the constitutional amendments; he remains forcibly disappeared. Similarly, opposition figure Alaa al-Khayyam of the Dostour Party was temporarily apprehended by security personnel and detained after he noted to a judge who had been monitoring a polling center in Beheira that pro-amendment flyers were being distributed outside of the location and in violation of election policies. Khaayam was released after being held for half an hour.

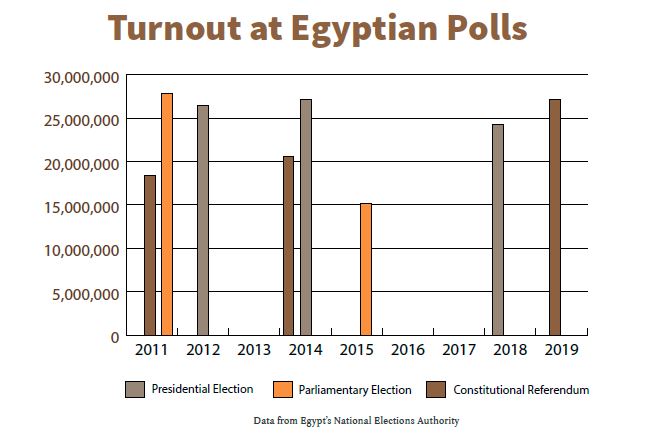

Though journalists were permitted access to polling centers during the referendum, some individuals reported misdirection from polling officials and intimidation tactics meant to convince voters not to participate in interviews with journalists about the referendum. Other journalists reported being banned from attending the tallying process of referendum votes. Few other independent bodies were present to officially monitor the referendum. Eleven domestic organizations and two international groups—West African Network for Peacebuilding and the Ma’ona Association for Human Rights and Immigration—were granted monitoring permission. This was a stark contrast to the 80 groups, including European Union officials, who monitored the constitutional referendum in 2014. Early polling tallies indicated a very high number of no votes in some areas—including one district in Damietta that registered 373 votes yes versus 981 votes no. Shortly after these initial indications, the NEA announced it would hasten its announcement of the results by several days, and would announce only a nationwide tally. The final figures indicated that over 27 million Egyptians voted in the elections—approaching turnout numbers similar to those seen in the 2012 and 2014 presidential elections, and a higher turnout than that of the 2014 referendum. Yet photos and reports from polling locations showed minimal participation or activity for the referendum. Furthermore, a breakdown of the total number of votes demonstrates that each polling center would have to have tallied on average one vote per minute. Additionally, some videos surfaced of security personnel coercing and threatening civilians into voting in the referendum.

Implications: Similar to previous national elections, Egypt’s 2019 constitutional amendments referendum was marred by practices meant to silence opposition voices and promote a specific government agenda, and the determination of participation rates and a final ballot count was not transparent. The rapid turnaround following parliamentary approval of the package into the referendum is indicative of the state’s attempt to disenfranchise its population by not allowing them suitable time to appropriately read, understand, and make an informed decision on the amendments. Further, the required in-person voting for expatriates constitutes a serious disenfranchisement, particularly for voters living far from one of the only 140 polling centers worldwide. Ultimately, the lead up to the referendum, the referendum itself, and the pronouncement of results are collectively representative of the state’s growing control over the political sphere amid an environment in which authorities act according to their specific agenda, rather than assessing, understanding, and representing the will of the Egyptian people.

TIMEP Coverage:

- “2019 Constitutional Amendments” (TIMEP Brief)

- “Draft Constitutional Amendments” (TIMEP Brief)

- “Potential Changes to Egypt’s Presidential Term Limits” (TIMEP Brief)

- “Amending Egypt’s Constitution” (TIMEP Infographic)

- “Egypt’s Constitutional Amendments: A Nail in the Coffin of Political Pluralism” (TIMEP Commentary)

- “Doubling Down on Dictatorship” (TIMEP Commentary)

- “Sisi’s power grab in Egypt gets a nod from Trump” (External Commentary)